AzamSharp

What I Learned While Building My Veggie Garden

A developer story about SwiftUI, gardening, and the things you only discover once you ship

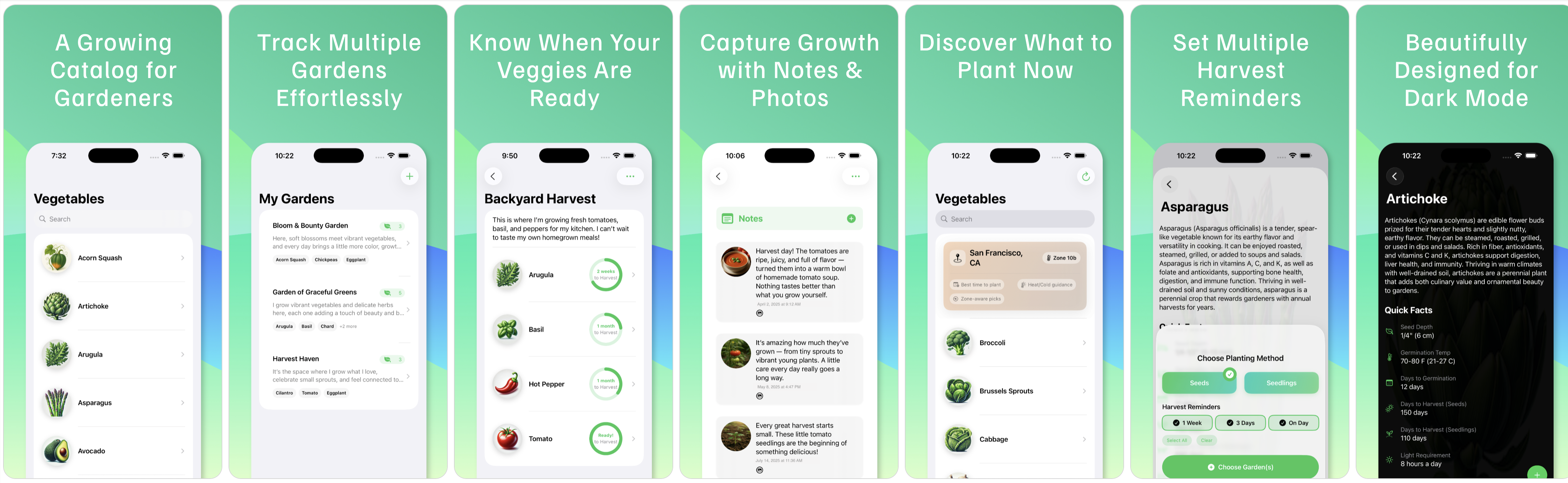

I recently released a new Vegetable Gardening app called My Veggie Garden. It is built with SwiftUI, SwiftData, and Foundation Models, and it has been one of the most rewarding projects I have worked on. Along the way I made mistakes, rewrote things, simplified things, and discovered a few lessons that I wish I had known earlier.

If you want to check out the app, you can find it here: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/my-veggie-garden/id6754995753

Here is a more personal look at what I learned.

Architecture is not just structure, it is clarity

In the early versions, I kept my data logic close to where it belonged. Everything related to my vegetable models such as calculating days passed or time until harvest lived inside my SwiftData models. This kept the code expressive and easy to follow.

From there I created a handful of services: Location Manager, Veggie Store, Store, Hardiness Zone Service, and a few others. Some of them kept state while others were simple helpers. Injecting everything through the Environment kept the app clean and made the data flow predictable. For a solo developer, predictable behavior is a gift.

Know your audience, not your wishlist

I love experimenting with new things, so I considered adding AR support, widgets, and even Watch features. I thought it would be cool. My users did not think so. When I looked at my earlier gardening app and listened to the feedback, people wanted one thing: a simple tool that helps them grow food.

They wanted clear planting instructions. They wanted reminders. They wanted a way to organize their gardens. Not flashy features. Not clever icons that needed a legend. If an icon confused people, I replaced it with a text label.

Your audience will always tell you what matters, but only if you are willing to listen.

Cutting offline support rebuilt the app

Originally every vegetable was stored with SwiftData. Once iCloud joined the party everything started to fall apart. Vegetables synced multiple times on different devices, and the app slowed down. I suspect the joins and the size of the model played a role.

I finally removed the vegetables from the database and stored them in a simple Observable Object that I injected through the Environment. There are around eighty to ninety vegetables and they barely take any space. More important, the app instantly felt faster and lighter.

This also cleaned up my data model. I now reference vegetables by an id instead of embedding the entire object.

Sometimes removing a feature feels like progress.

Caching matters more than you think

Since I manage my own server built with ExpressJS, I can send a 304 response when nothing has changed. This alone made the app feel snappier. For images I leaned on Kingfisher, which made caching effortless.

Small optimizations like these add up. Slow apps feel heavy, fast apps feel cared for.

Resize user photos, and your future self will thank you

People love attaching photos of their plants. But syncing original resolution images across devices is slow and expensive. I resize the photos before syncing so the user sees a sharp picture but the app does not overload iCloud. I still let them save the original photo to their own library so nothing is lost.

Do not use Foundation Models to predict hardiness zones

One of the main features in the app is the ability to use latitude and longitude to determine the local hardiness zone and then recommend vegetables that can be planted at that moment.

I tried using Foundation Models to guess the zone. It was exciting, but it was wrong. Repeatedly wrong. Eventually I switched to real USDA zone data and paired the correct zone with an AI generated recommendation. That combination worked perfectly.

AI is powerful, but it still needs good data.

Always prepare a fallback view for older devices

Apple Intelligence will not run on every device. If you rely on models or AI related features, make sure the app still feels complete on devices that cannot use those features. A simple friendly fallback view goes a long way.

No hard paywalls

My approach was simple. People can use the entire app, but they only get access to five vegetables in the free version. There is no sudden wall, no blocked screen, no rude prompt. They can explore at their own pace.

This made people trust the app more, and trust is more valuable than conversions.

StoreKit 2 is surprisingly pleasant

StoreKit 2 along with the In App Purchase configuration file made testing and integration very smooth. Sandbox testing works well and allowed me to catch issues before release.

Apple Store Server Notifications are your friend

Apple provides a notifications API that sends events whenever something changes with a users subscription. It is very easy to set up. With ngrok you can even test the entire flow locally. Once the event arrives, you can forward it to Slack or any other tool your team uses.

AI coding tools are incredible

ChatGPT helped me refine views, improve logic, explore alternatives, and debug ideas. Creating a dedicated project inside ChatGPT kept all my prompts in one place. It felt like having a design and architecture assistant who never gets tired.

Simple feature flags win

Instead of creating a complex system, I did something very straightforward. I hardcoded which vegetables are free. That is it. It makes the code easier to maintain and keeps the logic obvious.

Beta testers are priceless

My testers found problems, suggested improvements, and confirmed decisions. Their feedback changed the app in meaningful ways. Never skip testing with real people.

Screenshots do not need to be your talent

I used AppScreens for all of my screenshots. It saved a lot of time and gave the app a polished look.

App icon powered by creativity and ChatGPT

I went through several icon concepts with ChatGPT. It even generated the asset files for me. What would have taken hours turned into a fun process.

Do not forget your legal links

Make sure your Terms of Service and Privacy Policy appear both in your In App Purchase screen and on your App Store page. Forgetting this will result in an instant rejection.

Marketing is harder than development

This may be the biggest lesson of all. Writing code is challenging but it feels natural. Marketing, on the other hand, feels like speaking a different language. You can build a beautiful app, test it carefully, and polish every corner, but if you cannot communicate its value, it will quietly sit in the App Store without ever reaching the people who would love it.

I spent countless hours experimenting with screenshots, rewriting descriptions, and trying to find the right balance between clarity and excitement. Social media moves fast. App Store search rankings are unpredictable. People scroll and forget. It can feel like shouting into the wind.

Marketing forces you to think about your app in human terms. What problem does it solve. Why should someone care. How can you explain your idea in one sentence while still sounding like yourself.

It is slow work. It requires patience. It demands humility. And it is easily more difficult than the development itself. But when someone discovers your app, uses it, and tells you it made their life better, all of that effort feels worth it.

Conclusion

Building My Veggie Garden taught me far more than how to structure SwiftUI views or fine tune a data model. It taught me how important it is to listen to users, to simplify when things become heavy, and to be patient when the work is not glamorous. It reminded me that great apps are not only written with clean code but also shaped by real people, honest feedback, and many small decisions that add up over time.

Most of all, this project showed me that the journey does not end when you ship. The real work begins when your app is in the hands of others and you continue learning, improving, and adjusting. Whether it is refining features, fixing small pain points, or trying to reach new users through marketing, every step teaches you something valuable.

I am grateful for the experience, grateful for the people who tested and supported the app, and excited to keep improving it. If you are building your own app, I hope some of these lessons help you on your own journey.