AzamSharp

Building Large-Scale Apps with SwiftUI: A Guide to Modular Architecture

Updated (10/10/2024)

- Added new section Testing Logic in SwiftUI Views

Updated (01/22/2024)

- Added “TabView Navigation”

Updated (08/31/2023)

- Added “Problems with MVVM with SwiftUI”.

- Updated “Understanding the MV Pattern”

- Updated “Navigation”

- Updated “Displaying Errors”

- Added “Formatting”

Updated (02/14/2025)

- Updated the article to include Store as an added term for aggregate models.

Software architecture is always a topic for hot debate, specially when there are so many different choices. Since 2022, I have been experimenting with MV pattern to build client/server apps and wrote about it in my original article SwiftUI Architecture - A Complete Guide to MV Pattern Approach. In this article, I will discuss how MV pattern can be applied to build large scale client/server applications.

Architecture and patterns depends on the type of application you are building. No single architecture will work in all scenarios. Choose the best architecture suitable for your application needs.

The outline of this article is shown below:

- Modular Architecture

- Problems with MVVM with SwiftUI

- Understanding the MV Pattern

- Screens vs Views

- Multiple Aggregate Models

- View Specific Logic

- Validation

- Navigation

- TabView Navigation

- Displaying Errors

- Grouping View Events

- Formatting

- Testing

If you are interested learning more about SwiftUI then check out my course SwiftUI Architecture - Patterns and Best Practices published on Teachable platform.

Note

In this article, I previously used the term aggregate model. Now, I refer to these models as Store. However, the underlying concept remains the same. The primary reason for this change was to eliminate confusion between client-side JSON model objects and observable objects (Store).

Modular Architecture

Modular architecture in software refers to the design and organization of software systems into small, self contained modules or components. These modules can be tested and maintained independently of one another. Each module serves a specific purpose and solve a specific business requirement.

Modular architecture also provides advantages when working on large projects consisting of multiple teams. Each team can work on a particular module, without interfering with each other.

If you are working on a module that will be consumed or used by other teams then make sure that you are communicating with them and not creating the module in complete isolation. A lot of problems in software development exists solely because of lack of communication between teams.

Modularity can be achieved in several different ways. You can expose each module as a package (SPM), which can be imported into different applications. Modularity can also be achieved by structuring your app based on specific grouping or folder structure. Keep in mind that when using folders for modularity you have to pay special attention to separation of concerns and single responsibility principles.

The focus of this article is not Swift Package Manager, but how to achieve modularity by breaking the app based on the bounded context of the application. Swift Package Manager can be used to package those dependencies into reusable modules.

Problems with MVVM with SwiftUI

MVVM pattern originated from Presentation Model architecture, which is known as Application Model to Visual Works Smalltalk users. The main idea behind the Presentation Model is that the state and the behavior of the view is pulled out to its own model. The Presentation Model communicates with the business logic layer and provides the data to the view. The view performs two way communication with the Presentation Model in which, the data can flow from the view to the Presentation Model and vice versa.

The main motivation for the Presentation Model is to provide an interface to the view so it can only get the data it needs, without directly dealing with the complicated business logic layer. Martin Fowler mentioned that one of the annoyances of Presentation Model is to write the synchronization code (binding) between the Presentation Model and the view. This was later resolved when Microsoft introduced WPF (Windows Presentation Foundation) framework. Windows Presentation Foundation consisted of built-in binding between the view (XAML) and view models (C#). Microsoft started calling it MVVM (Model View View Model).

In the conventional MVVM pattern, alongside the creation of a new view designed to function as a screen, a corresponding view model is also crafted in parallel. The view model’s role is to manage bindings, handle network operations (using a network layer), manage validations, among other tasks. Imagine an application focused on presenting a list of movies from an API, affording users the ability to append new movies, and exhibiting comprehensive movie details. To architect such an application adhering to the MVVM pattern, you may end up with the following structure.

| View | View Model |

|---|---|

| MovieListView | MovieListViewModel |

| AddMovieView | AddMovieViewModel |

| MovieDetailView | MovieDetailViewModel |

Each view is represented by its own view model. Consider an application that consists of 20+ screens, you will end up with 20+ view models. A typical view model can consists of networking code (through a networking layer), UI validation and data transformation code. Each of these view models conforms to ObservableObject protocol. The main purpose of ObservableObject protocol is to define a new source of truth. Source of truth is one of the most important concepts in SwiftUI as it is responsible for keeping the data and the view in-sync. In a client/server application, source of truth is the server. So, if the source of truth is the same, why are we creating new source of truths for each view by introducing a view model by conforming to ObservableObject protocol.

This does not imply that you have to restrict yourself to just one

ObservableObjector source of truth for your entire application. While you can certainly incorporate multiple ObservableObjects into your application, their introduction should not be solely driven by the inclusion of a new view. The primary motivation behind introducing a new ObservableObject should stem from the integration of a new source of truth. Furthermore, you’ll come to understand that there are instances where you’ll introduce ObservableObjects based on the bounded context of the application. This is covered later in this article.

Another concerns arises from the fact that in a client/server application, most of these view models will need to communicate with the server. So, if you have a dozen screens and each screen is accompanied with a designated view model then it means you need to inject the networking layer to each of those view models using the principles of dependency injection. This can result in the following implementations:

struct MoviesApp: App {

var body: some Scene {

// httpClient can take HTTPClientProtocol

MovieListView(vm: MovieListViewModel(httpClient: HTTPClient()))

}

}

MovieListView depends on MovieListViewModel which depends on HTTPClient. The main issue is not the dependency injection but that you have to do this for every view that consists of a view model and wants to communicate with the server. Consider repeating the same steps for AddMovieView and MovieDetailView. This can make your code extremely hard to understand and with each ObservableObject you have created a new source of truth. With dozens of sources of truth, it becomes hard to manage and share state between different views in a client/server applications.

But the most important point is that the functionality offered by a view model is already baked into the view. The primary responsibility of a view model is to support binding. This is already possible inside the view through the use of @State, @Binding, @EnvironmentObject property wrappers.

It’s important to reiterate that this does not imply a shift towards placing all elements within a view. The integration of an

ObservableObjectis warranted when a new source of truth emerges. However, the inclusion of anObservableObjectshouldn’t be prompted solely by the addition of a new view. Consider an example ofLocationManager. The purpose of aLocationManageris to provide the user with a new location, region, coordinates etc. This is a good candidate for anObservableObject.

Now, let’s move our focus to the view. I strongly believe that Apple did a disservice to the iOS community by calling it a view. They should have called it a component or something similar. The word view entails that it is a visual only component like HTML in web development or XAML in WPF. But that is not the case. The view in SwiftUI is the return from the body property. Even that is not an actual view but just the declaration of the view.

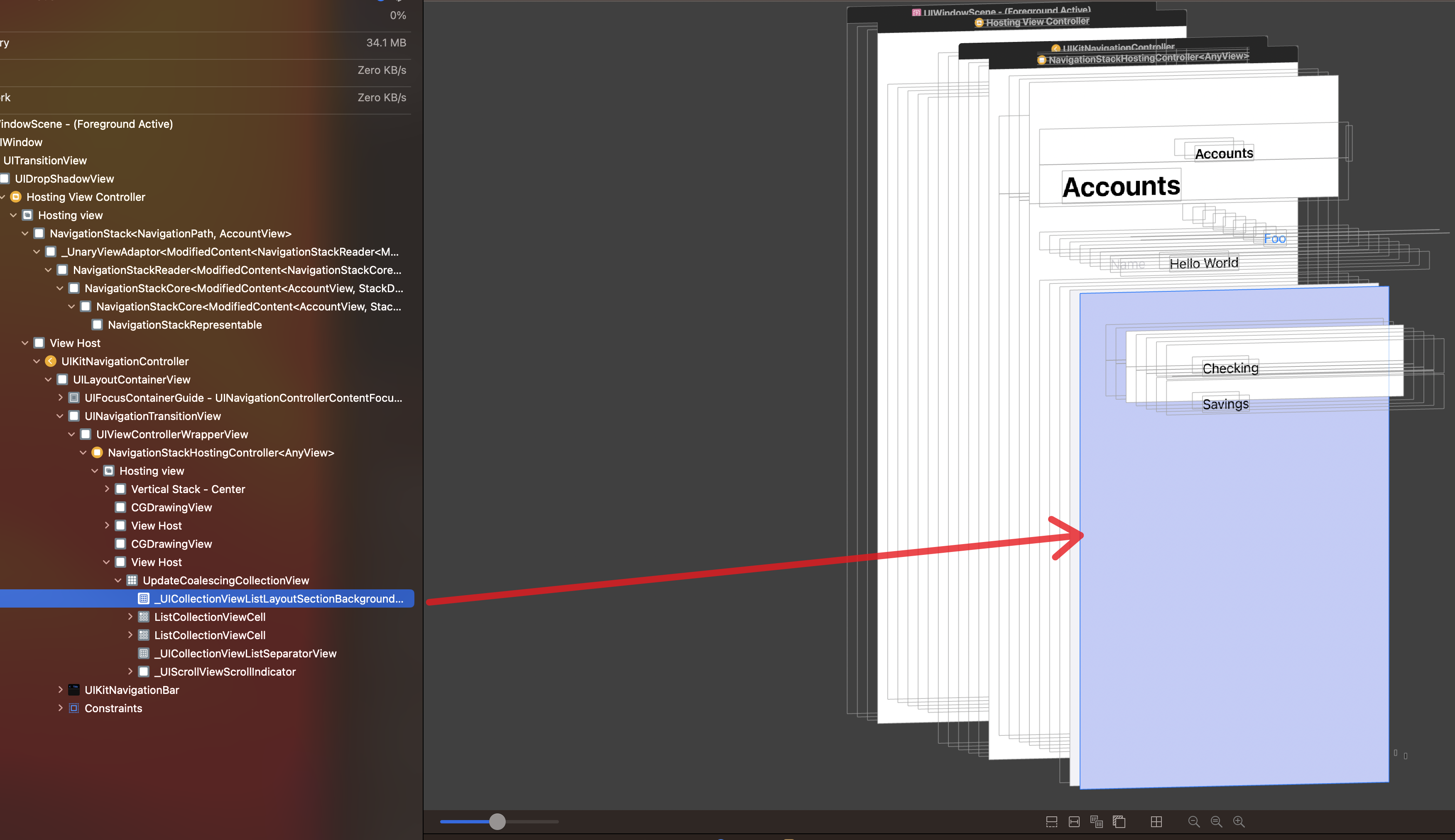

SwiftUI views are mapped to the UIView counter parts and then rendered on the screen. SwiftUI views are just basic value type structs. They have no knowledge on how to paint pixels on the screen. SwiftUI uses the declaration of the views to render actual UIViews. Below you can find some common mapping from SwiftUI views to UIKit views:

| SwiftUI View | UIView |

|---|---|

| List | UICollectionView |

| Text, Button | CGDrawingView |

| TextField | UITextField |

All this mapping is hidden from the developers but you can always look at the inner details through the view debugging feature in Xcode. Below you can see through view debugging that List in SwiftUI maps to UICollectionView.

The views in SwiftUI, reminds me of ReactJS JSX syntax. Let’s take a look at a very small example.

function App() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello World</h1>

<button>Save</button>

</div>

)

}

In the above ReactJS code, we have created a functional component called App. The App component returns a <div> element containing a <h1> and <button>. The thing to notice here is that those are not actual HTML elements. Those are virtual DOM (Document Object Model) elements managed by React framework. The main reason is that React needs to track changes to those elements so it can only render, what has changed. Once React finds out the changed elements using the diffing process, those virtual DOM elements are used to render real HTML elements on the screen.

SwiftUI uses the same concepts internally. The views in the body property are not actual views but the declaration of views. Eventually, those views gets converted to real views and then displayed on the screen. John Sundell also talked about it in his article SwiftUI views versus modifiers.

If you are interested in learning more about the concept of virtual DOM then check out this talk title Tom Occhino and Jordan Walke: JS Apps at Facebook. This is the talk, where Facebook introduced ReactJS to the public.

For three years, I’ve employed the conventional MVVM approach alongside SwiftUI, but consistently encountered struggles with the framework. I regrettably overlooked Apple’s beneficial property wrappers, attempting instead to create solutions from scratch. This misguided effort led to increased complications, a surplus of code, and heightened maintenance demands. It was during this period that I realized the imperative for a more effective strategy.

Understanding the MV Pattern (SwiftUI Built-In Architecture)

The main idea behind the MV pattern is to allow views directly talk to the model. In MV pattern, views are the view model. This eliminates the need for creating unnecessary view models for each view, which simply contributes to the size of the project but does not provide any additional benefits. Keep in mind that every single line of code you write also needs to be maintained. This means that your code is not an asset but a liability.

MV pattern does not advocate putting all the business logic inside a view. That particular pattern is known as Container Pattern. I have also talked about it on my blog. You can read about it here.

MV pattern can take different forms depending on the type of app you are writing. This article is mainly focused on a client/server apps, where a SwiftUI app serves as a client.

Although there is no official name for this pattern, I have seen most people call it MV Pattern since it does not include an extra layer of view models. This pattern has originated from Apple’s documentation and code samples.

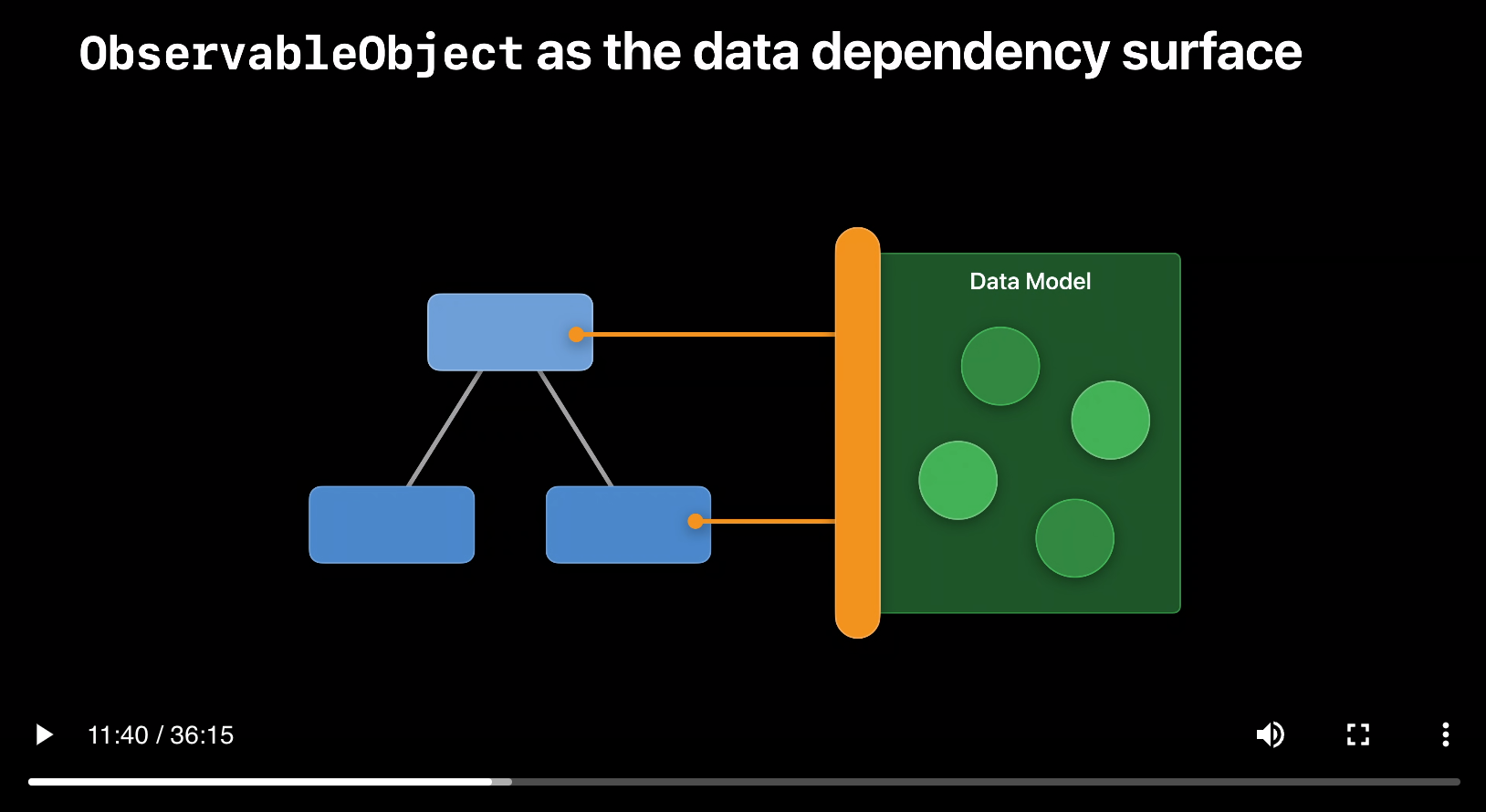

In WWDC 2020 talk titled Data Essentials in SwiftUI Apple presented the following diagram.

The central concept revolves around granting views access to a unified layer or interface, which functions as the definitive source of information and grants entry to all components within the application. On occasions, this unified layer might correspond to the network layer. This approach is advisable in situations where your views autonomously consume the data, and making alterations to the data doesn’t necessitate synchronization with other segments of your application. A straightforward example could involve a third-party service that furnishes a list of up-to-date news articles. In this case, your view can directly interact with the network layer to showcase the news articles. This concept is illustrated below:

struct NewsListScreen: View {

@Environment(\.httpClient) private var httpClient

@State private var articles: [Article] = []

private var sortedArticles: [Article] {

articles.sorted { lhs, rhs in

// sorting logic

}

}

private func loadArticles() async {

let resource = Resource(Constants.Urls.articles)

do {

try articles = httpClient.load(resource)

} catch {

// handle error

}

}

var body: some View {

List(sortedArticles) { article in

ArticleView(article)

}.task {

await loadArticles()

}

}

}

The NewsListScreen serves as a container view. This means it is responsible for making network calls and fetching the data. Once the data is fetched, it can be passed down to the presentation view. At present the only reusable view we have in the above code is ArticleView. Depending on your app and requirements, you can also extract out List into a separate ArticleListView component.

Another thing to notice in the above code is the use of sortedArticles private property. As I mentioned earlier that in MV Pattern, views are the view models. This is no need to create a view model associated with NewsListScreen. If your view is getting large then use the principles of view decomposition to break it into smaller pieces. Keep in mind that views in SwiftUI are value types. Value types are cheap to create. This gives you the flexibility to break your views into multiple reusable pieces.

If you are wondering how would you test the sortedArticles property then keep reading. Testing will be covered in the later section of this article.

The above technique is ideal when the state is private to the view and is not shared with the rest of the application. You can still alter/modify the state by passing the state to child views using @Binding and @Bindable property wrappers and macros, but once you are passing the state into multiple levels of view hierarchy it becomes repetitive and time consuming.

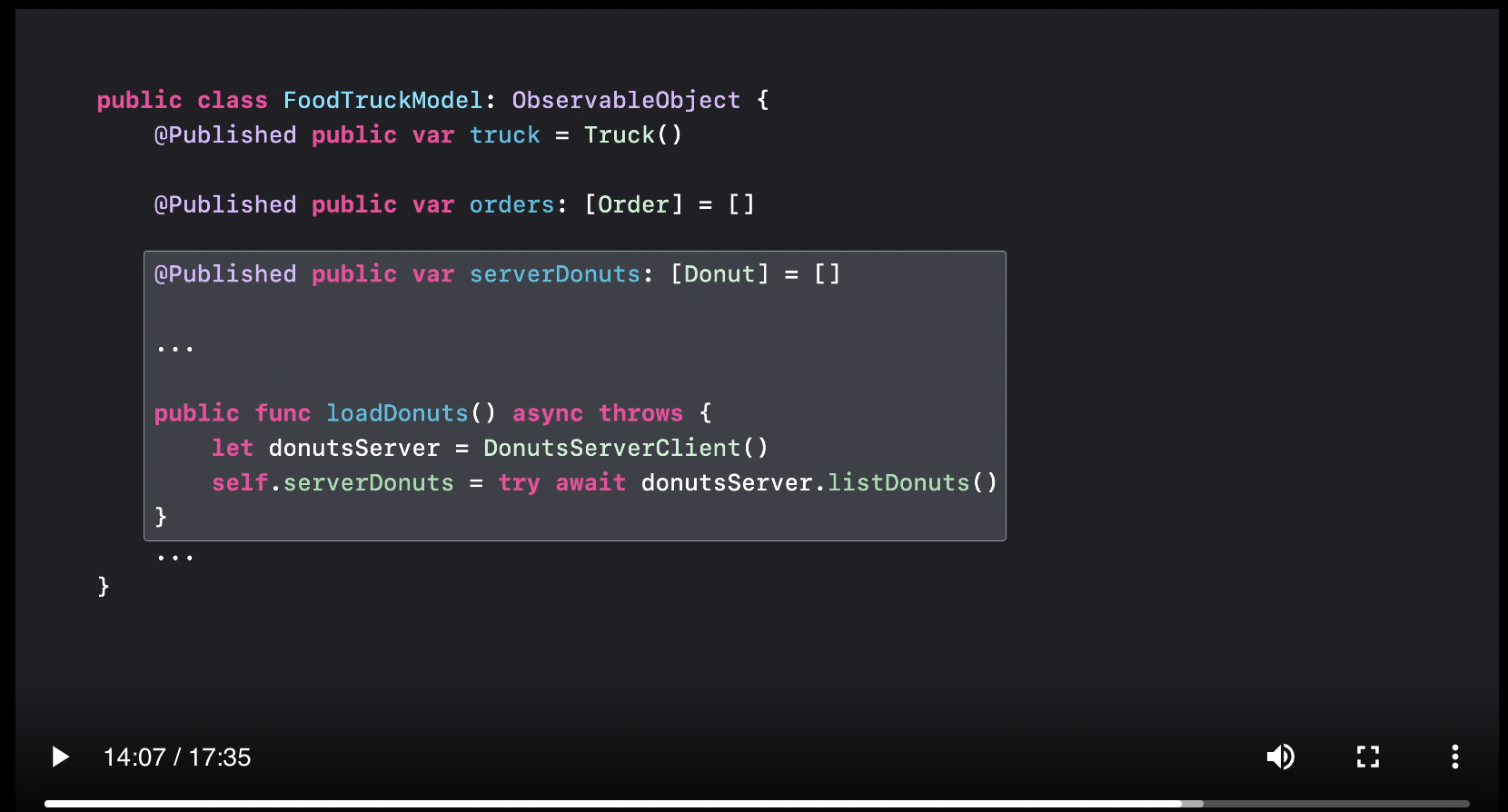

When working on larger apps, you need the ability to share state with other views of the application without having to pass down through the view hierarchy. Apple has demonstrated this approach in few sample projects, which includes Fruta and FoodTruck. These sample applications demonstrated how to use this pattern against a hard-coded data source. But in WWDC video title “Use Xcode for server-side development“ Apple showed how to update the existing FoodTruck app and consume the data from an API response.

The screenshot below shows FoodTruckModel using the DonutsServerClient to retrieve list of donuts. DonutsServerClient is responsible for making an actual request to the server and downloading the donuts. Once the donuts are downloaded they are assigned to the serverDonuts property maintained by the FoodTruckModel.

Use Xcode for server-side development

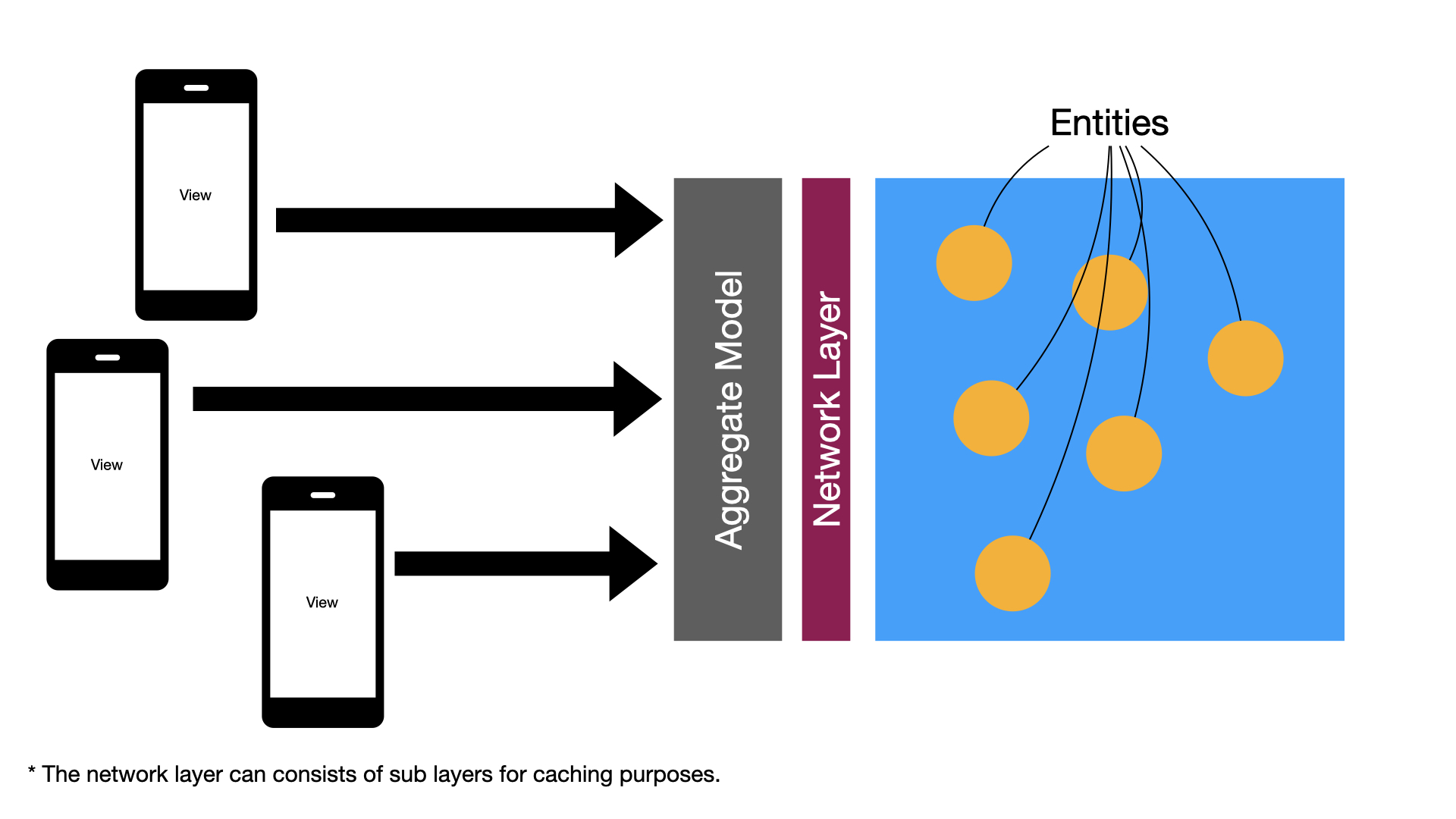

Here is the updated diagram to support the networking layer.

I know what you are thinking. Are we going to take advice based on Apple’s code samples blindly? No! Never take any advice blindly. Always invest time and research and weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each approach. I have evaluated many different techniques and patterns and found this to be the best and simplest option when building SwiftUI applications. Do your research!.

Based on Apple’s recommendation in their WWDC videos and code samples and my own personal experience, I have been implementing a single aggregate model/store, which holds the entire state of the application. For small and medium sized apps, a single aggregate model/store might be enough. For complicated apps, you can have multiple aggregate models/stores which will group related entities together. Multiple aggregate models/stores are discussed later in this article.

Once again keep in mind that this article is about client/server apps. If you are using Core Data or anything else then you will have to do your research. For purely Core Data apps, I have been experimenting with Active Record Pattern. You can read about it here.

Following the pattern discussed in Use Xcode for server-side development talk, here is the StoreModel I have implemented for my application.

@MainActor

@Observable

class FoodTruckStore {

let httpClient: HTTPClient

private(set) var products: [Product] = []

private(set) var orders: [Order] = []

init(httpClient: HTTPClient) {

self.httpClient = httpClient

}

// Computed property to get premium products

var premiumProducts: [Product] {

products.filter { $0.isPremium }

}

// Computed property to get top-selling products

var topSellingProducts: [Product] {

products.sorted { $0.salesCount > $1.salesCount }

}

// Computed property to get most recent orders

var mostRecentOrders: [Order] {

orders.sorted { $0.createdAt > $1.createdAt } // Sort by creation date in descending order

}

// Load all products

func loadAllProducts() async throws {

let resource = Resource(url: Constants.Urls.products, modelType: [Product].self)

products = try await httpClient.load(resource)

}

// Save a new product

func saveProduct(_ product: Product) async throws {

let resource = Resource(url: Constants.Urls.createProduct, method: .post(product.encode()), modelType: CreateProductResponse.self)

let response = try await httpClient.load(resource)

if let product = response.product, response.success {

products.append(product)

} else {

throw ProductError.operationFailed(response.message ?? "")

}

}

// MARK: - Orders Functionality

// Load all orders

func loadAllOrders() async throws {

let resource = Resource(url: Constants.Urls.orders, modelType: [Order].self)

orders = try await httpClient.load(resource)

}

}

FoodTruckStore is an aggregate model or store that centralizes all the data for the application. Views communicate directly with the FoodTruckStore to perform queries and persistence operations. FoodTruckStore also utilizes HTTPClient, which is used to perform network operations. HTTPClient is a stateless network layer. This means it can be used in other parts of the application that are not SwiftUI, meaning UIKit or even on a different platform (macOS).

In Domain-Driven Design (DDD), an aggregate is a cluster of related objects that are treated as a single unit of work for the purpose of data consistency and transactional boundaries. An aggregate model, then, is a representation of an aggregate in code, typically as a class or group of classes.

FoodTruckStore can be used in a variety of different ways. You can use FoodTruckStore as a @StateObject if you only want the data available to a particular view and if you want to tie the object with the lifetime of the view. But quite often I find myself adding FoodTruckStore to @EnvironmentObject so that it can be available in the injected view and all of its sub views.

@main

struct StoreAppApp: App {

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView()

.environmentObject(FoodTruckStore(httpClient: HTTPClient()))

}

}

}

After the FoodTruckStore is injected through the @EnvironmentObject, you can access the FoodTruckStore as shown in the implementation below.

struct ContentView: View {

@EnvironmentObject private var store: FoodTruckStore

var body: some View {

ProductListView(products: store.products)

.task {

do {

try await store.populateProducts()

} catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

}

}

}

You might be tempted to use

@EnvironmentObjectinside all the views. Although, it will work as expected but for larger applications you need to make presentation views free of any dependencies. Presentation views are usually child views that are created for the purpose of reusability. It you try to access@EnvironmentObjectinside the child views then it effects their reusability status and they become less useful. The main reason is that now they are dependent on the@EnvironmentObjectto provide data to them. Instead we should follow the top-down approach, where the data is passed from the parent view to the child view. This is also known as the Container/Presentation pattern. Having said that sometimes views can be self contained, meaning they are always used in a certain way. In those situations child views can directly access@EnvironmentObject.

Apart from fetching and persistence, FoodTruckStore can also provide sorting, filtering, searching and other operations directly to the view.

If I was using the traditional MVVM pattern then we would create several view models to accommodate each screen. This can include

ProductListViewModel,AddProductViewModel,ProductDetailViewModeland many more. Most of the time, these view models end up with one or two functions and maintaining a single source of truth can become very hard. In MV pattern, the view itself is the view model so we don’t need to create unnecessary view models for most of the time. The view, which is also a view model is simply going to ask model (Aggregate Model/Store) for the data.

The source of truth in a client/server application is the server.. This means you should not be adding view models conforming to ObservableObject (new source of truth) protocol just because you added a new view. The source of truth for that view has not changed, it is still the server.

A single FoodTruckStore is ideal for small or even medium sized apps. But for larger apps it will be a good idea to introduce multiple aggregate models/stores based on the bounded context of the application. In the next section, we will cover multiple aggregate models/stores and how they benefit when working in large teams.

The MV pattern and MVVM pattern may appear similar at first glance, but they exhibit significant differences. In a client/server app using MVVM, a separate view model is created for each screen. For instance, in a movies management app, you might end up with multiple view models like MovieListViewModel, AddMovieViewModel, MovieDetailViewModel, and possibly MovieViewModel.

However, MV takes a different approach altogether, omitting the creation of view models. Instead, it directly binds the DTO objects (models from the server) to the view. In some cases, the view can directly utilize the network layer to fetch the DTO objects, while in others, a single Store (ObservableObject) or Aggregate Model (ObservableObject) aids in accessing the movies. Any required UI validation or data transformation is implemented within the view itself.

To ensure reusability of child views, the container and presenter pattern come into play. One view is responsible for requesting and obtaining the data, while another view, known as the presenter, takes charge of displaying the data. This separation of responsibilities ensures a more modular and maintainable design.

With MV, the overall structure differs from MVVM, allowing for a more direct handling of data and views without the need for multiple view models. By leveraging the container and presenter pattern, your app can achieve better organization and reusability of views.

Multiple Aggregate Models/Stores

As you learned in the previous section, the purpose of an aggregate model/store is to expose data to your view. As Luca explained in Data Essentials in SwiftUI WWDC 2020 (11:30) that @ObservableObject is your data dependency surface. Views can directly access the object and get the required data.

As your business grows, a single aggregate model/store might not be enough to maintain the life cycle and side effects of an entire application. This is where we will introduce multiple aggregate models/stores. These aggregate models/stores are based on the bounded context of the application. Bounded context refers to a specific area of the system that has clear boundaries and is designed to serve a particular business purpose.

In an e-commerce application, we can have several bounded contexts including checkout process, inventory management system, catalog, fulfillment, shipment, ordering, marketing and customer management modules.

Defining bounded context is important in software development and it helps to break down the application into small manageable pieces. This also allows teams to work on different parts of the system without interfering with each other.

Developers are usually not good in finding bounded context for software applications. The main reason is that their technical knowledge does not directly map to domain knowledge. Domain knowledge requires different set of skills and a domain expert is a better suited for this kind of role. A domain expert is a person, who may not be tech savvy but understands how the business or a particular domain works. In large projects, you may have multiple domain experts, each handling a different business domain. This is why it is extremely important for developers to communicate with domain experts and understand the domain before starting any development.

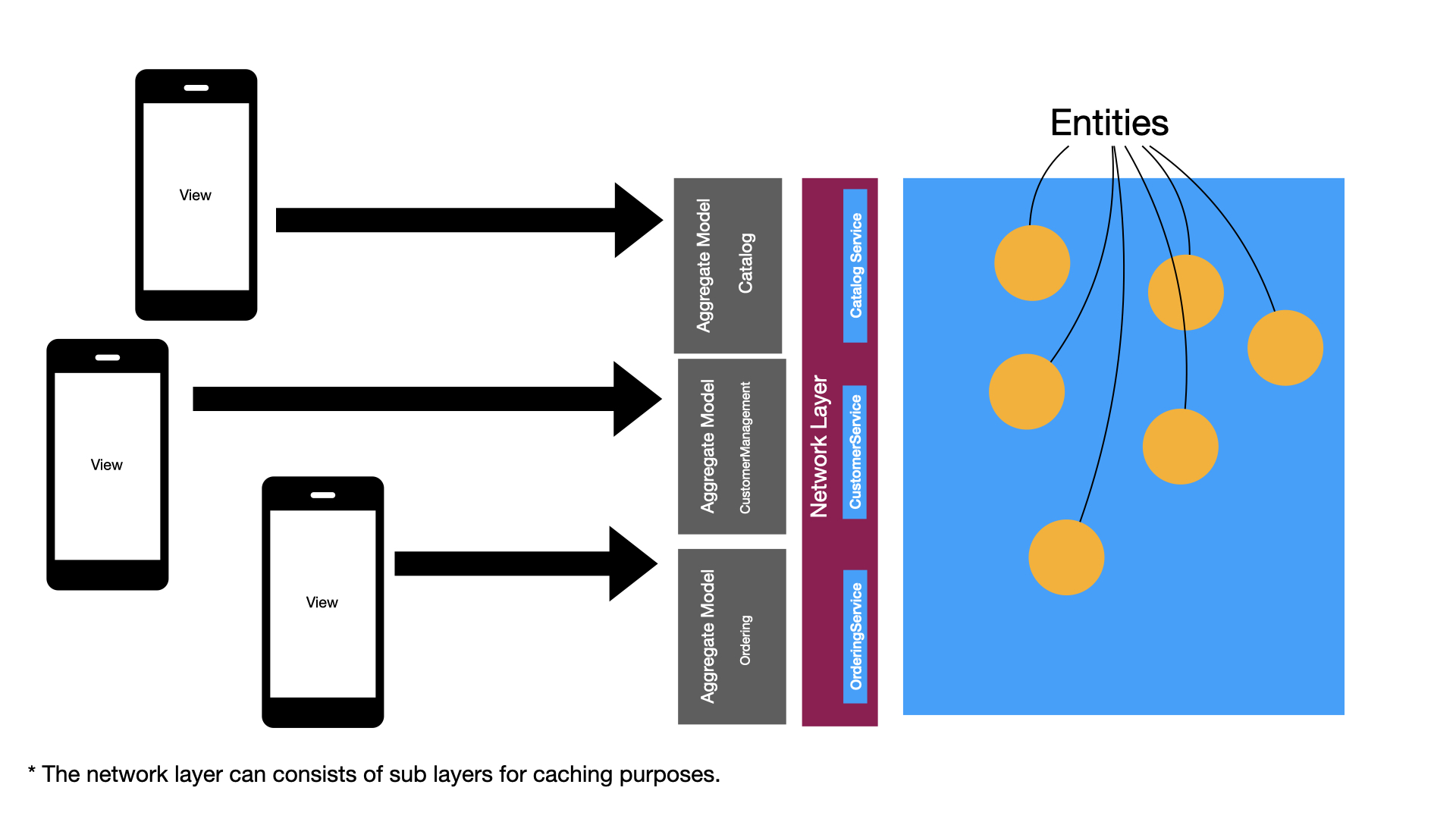

Once, you have identified different bounded contexts associated with your application you can represent them in the form of aggregate models/stores. This is shown in the diagram below.

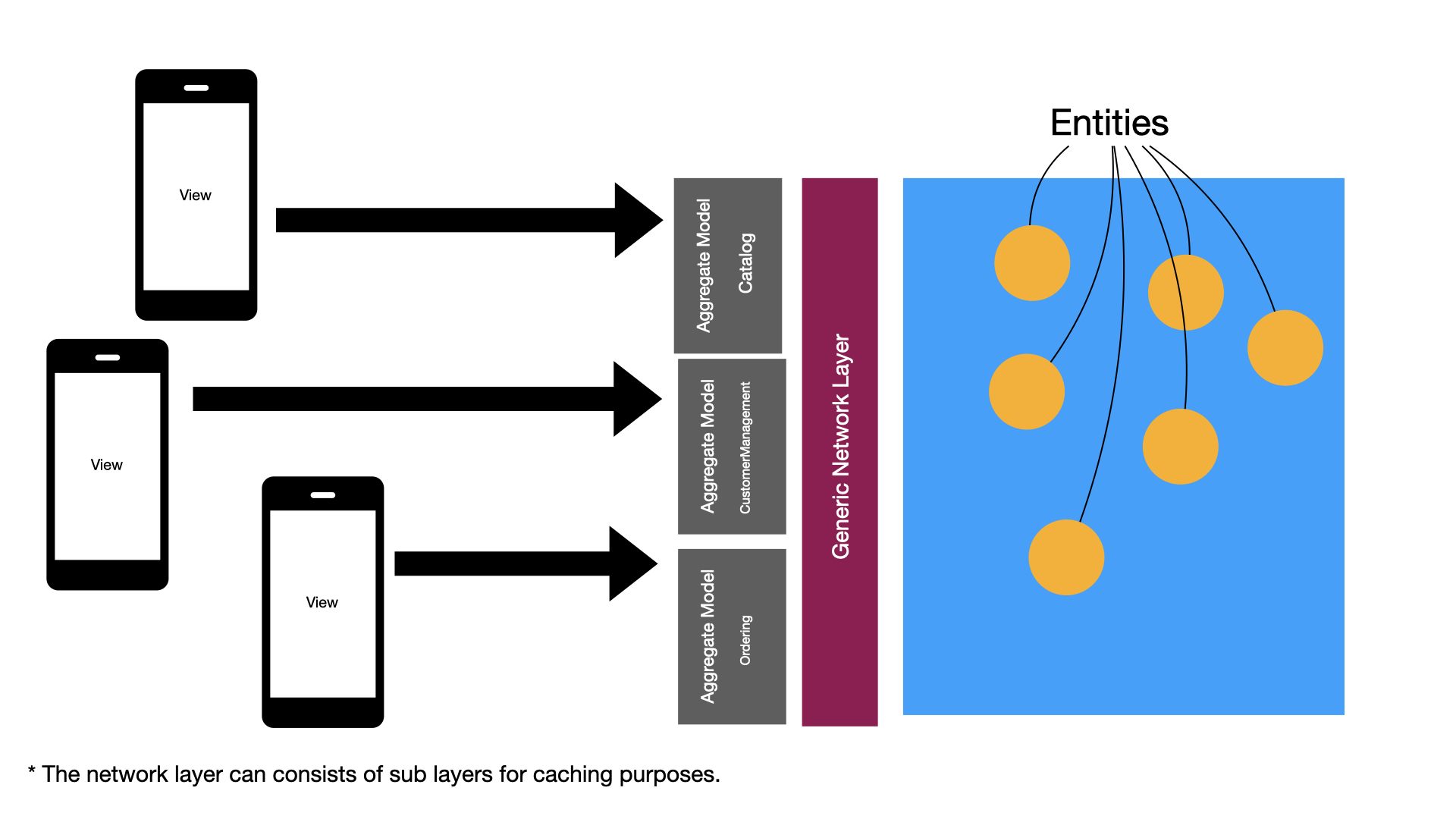

The network layer can also be divided into multiple HTTP clients or you can use a single generic network layer for your entire application. This is shown in the following diagram.

The Catalog aggregate model/store will be responsible for providing views with all the entities associated with Catalog. This can include but not limited to:

- Product

- Category

- Brand

- Review

The Ordering aggregate model/store will be responsible for providing views with all the ordering related entities. This can include but not limited to:

- Order

- OrderLineItem

- OrderStatus

- ShippingMethod

- Discount

The CatalogStore and OrderingStore aggregate models/stores will be reference types conforming to ObservableObject protocol. And all the entities they provide will be value types.

The outline of CatalogStore aggregate model/store and Product entity is shown below:

struct Product: Codable {

let productId: Int

let name: String

let category: Category

let price: Double

let description: String

let reviews: [Review]?

}

@MainActor

class CatalogStore: ObservableObject {

// designated or generic HTTP client

let httpClient: HTTPClient

@Published var products: [Product]

@Published var categories: [Category]

init(hTTPClient: HTTPClient) {

self.hTTPClient = httpClient

}

func loadProducts() {

products = httpClient.loadProducts

}

func getProductById(_ productId: Int) -> Product? {

// fetch product by id

}

func getProductsByCategory(_ categoryId: Int) -> [Product] {

// get products by category

}

func getCategories() -> [Category] {

categories = httpClient.loadCategories()

}

}

Catalog and Ordering aggregate models/stores are injected into the application as an environment object. You can inject them directly in your application root view or the root view of each section of the application. The later is shown below:

@main

struct StoreApp: App {

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView()

.environmentObject(CatalogStore(httpClient: HTTPClient()))

.environmentObject(OrderingStore(httpClient: HTTPClient()))

}

}

}

Now, inside a view you can use CatalogStore and OrderingStore models by accessing it through @EnvironmentObject. The implementation is shown below:

struct CatalogListScreen: View {

@EnvironmentObject private var catalogStore: CatalogStore

var body: some View {

List(catalogStore.products) { product in

Text(product.name)

}.task {

do {

try await catalogStore.loadProducts()

} catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

}

}

}

If your view needs to access ordering information then it can utilize the OrderingStore too.

struct AdminDashboardScreen: View {

@EnvironmentObject private var catalogStore: CatalogStore

@EnvironmentObject private var orderingStore: OrderingStore

var body: some View {

VStack {

List(catalogStore.products) { product in

Text(product.name)

}

List(orderingStore.allOrders) { order in

Text(order.status)

}

}.task {

do {

try await catalogStore.loadProducts()

try await orderingStore.loadOrders()

} catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

}

}

}

There are scenarios when your aggregate model/store will need to access information from another aggregate model/store. In those cases, your aggregate model/store will simply use the network service to fetch the information that is needs.

It is important that your caching layer is called from within the network layer and not from aggregate models/store. This will allow aggregate models/stores to take advantage of caching through the network layer, instead of implementing it on their own. By accessing caching layer from inside the network layer, all your aggregate models/stores can benefit from faster response through the use of cached resources.

As mentioned earlier for small or even medium sized apps, you may only need a single aggregate model/store. For larger apps you can introduce new aggregate models/stores. Make sure to consult with a domain expert before creating application boundaries.

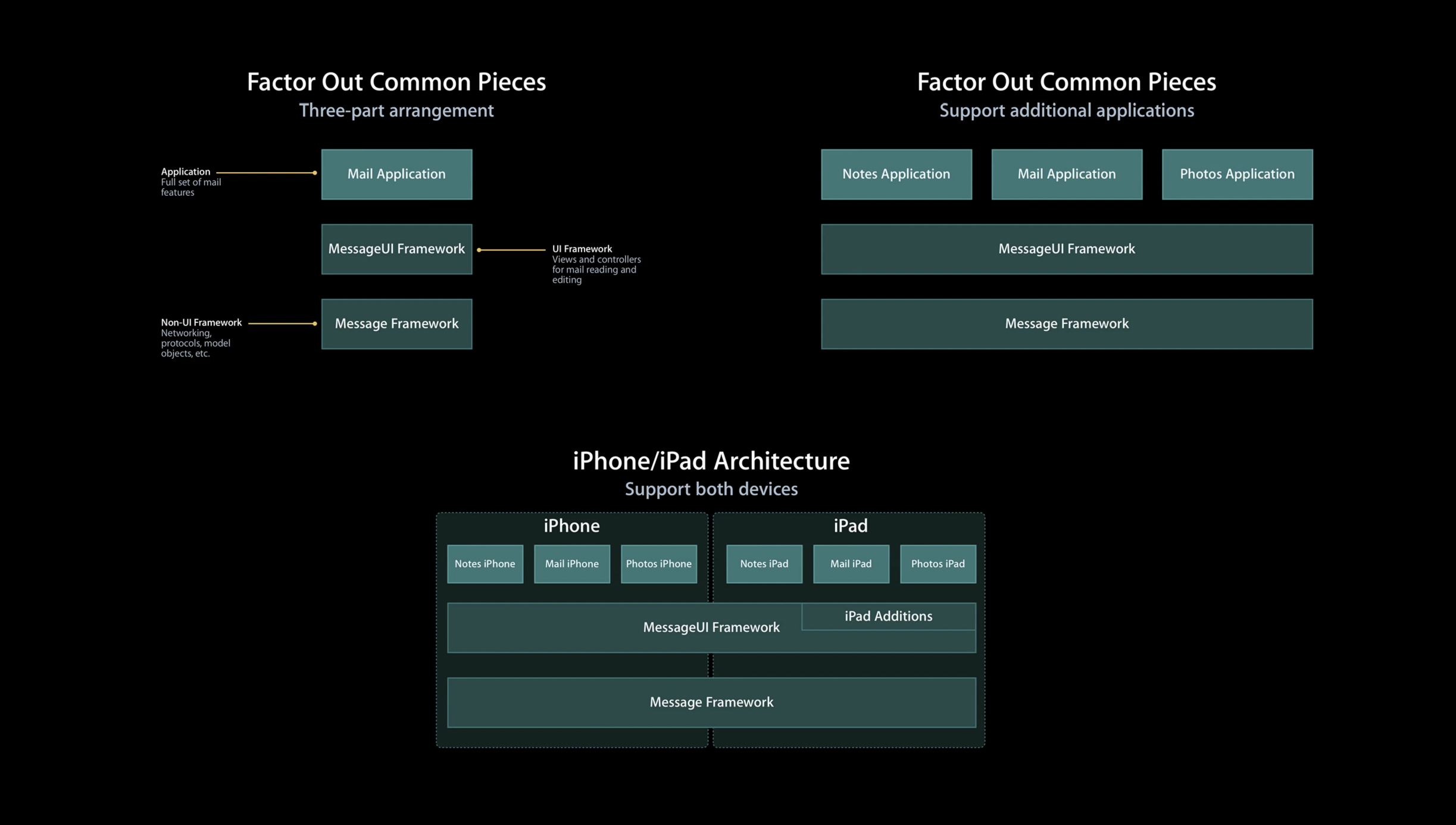

The concept of domain boundaries can also be applied to user interfaces. This allows us to reuse user interface elements in other applications.

- Permission has been granted from the original author of the image to use it in this article.

You can factor out common interface elements using Swift Package Manager and import those packages into other applications.

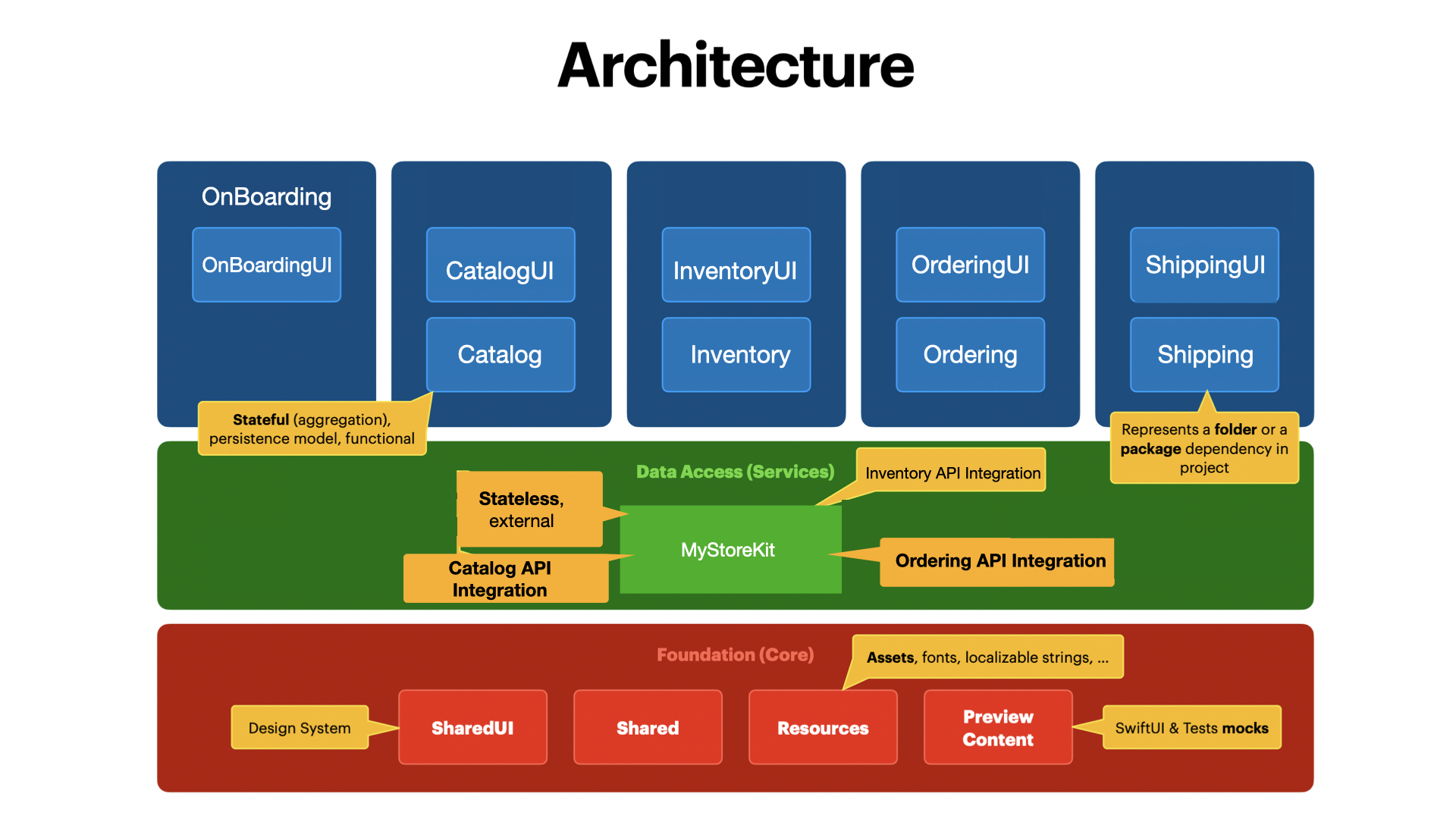

Let’s go ahead and zoom out and see how our architecture looks like with all the pieces in place.

- This image has been updated and the permission has been granted from the original author of the image to use it in this article.

As discussed earlier, each bounded context is represented by its own module. These modules can be represented by a folder or a package dependency.

CatalogUI: Represents user interface associated with catalog. This can include all the catalog specific stuff like AddCatalogScreen, UpdateCatalogScreen etc.

Catalog (CatalogStore): Represents the models associated with catalog. This will contain the aggregate model/store and all the entities exposed by the aggregate model/store.

MyStoreKit: Represents the HTTP client for performing network calls.

Foundation Core: Represents resources used by all modules. This can include helper classes/structs, reusable views, images, icons and even preview content used for testing.

Each module like Shipping, Inventory, Ordering etc can be represented by a folder structure or a package dependency. This really depends on your needs and if you wish to reuse your modules in other projects.

Using this architecture, future business requirements and data access services can be added without interfering with existing ones. This also allows more collaborative environment as different teams can work on different modules without interfering with each other.

View Specific Logic

In this last section, I talked about how aggregate models/stores can serve as a single source of truth and provide required data to the views. But what about view specific logic? Where should that logic be placed and what options do we have to perform testing on that logic.

In the code below, we want to filter the products based on the minimum and maximum price. The implementation is shown below:

struct ContentView: View {

let httpClient: HTTPClientProtocol

@State private var products: [Product] = []

@State private var min: Double?

@State private var max: Double?

@State private var filteredProducts: [Product] = []

private func filterProducts() {

guard let min = min,

let max = max else { return }

filteredProducts = products.filter {

$0.price >= min && $0.price <= max

}

}

private var isFormValid: Bool {

guard let min = min,

let max = max else { return false }

return min < max

}

var body: some View {

VStack {

HStack {

TextField("Min", value: $min, format: .number)

.textFieldStyle(.roundedBorder)

TextField("Max", value: $max, format: .number)

.textFieldStyle(.roundedBorder)

}

Text("Max must be larger than min.")

.frame(maxWidth: .infinity, alignment: .leading)

.font(.caption)

.padding([.bottom], 20)

Button("Apply") {

filterProducts()

}

.disabled(!isFormValid)

List(filteredProducts.isEmpty ? products: filteredProducts) { product in

HStack {

Text(product.title)

Spacer()

Text(product.price, format: .currency(code: "USD"))

}

}

.task {

do {

products = try await httpClient.loadProducts()

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}.padding()

}

}

struct ContentView_Previews: PreviewProvider {

static var previews: some View {

ContentView(httpClient: HTTPClientStub())

}

}

If filterProducts or similar functions will be involved in any model logic then you can also put it inside the aggregate root model/store, instead of the view.

Please note that instead of invoking the real service, we are using a stubbed version of the HTTPClient that returns pre-configured response. Another good option would be to create separate JSON files for each response and read data from those files, when using Xcode previews. I covered that in one of my YouTube video, Building SwiftUI Xcode Previews Using JSON File.

Keep in mind that in the above scenario, if no results are found during filtering then the original products array is returned.

We have two pieces of code in the view that constitute as logic, isFormValid and filterProducts. If we want to test that code we have number of ways.

Use Xcode previews! I know this does not sound fancy but I encourage you to use Xcode previews to test your view based logic. Xcode previews is extremely fast (depending on the machine you are using) and it gives you the same feeling as Red/Green/Refactor cycle. For this particular scenario, Xcode previews will be my first choice.

Xcode previews is not the answer to everything. If you are dealing with complicated view logic then it will be a good idea to move out all the logic into a separate struct and then write unit tests for that piece of code. Remember, one of the important aspects of why we test is to gain confidence about our code.

Another option is to extract the logic from the view and then write unit tests against it. This is shown in the implementation below:

struct ProductFilterForm {

var min: Double?

var max: Double?

func filterProducts(_ products: [Product]) -> [Product] {

guard let min = min,

let max = max else { return [] }

return products.filter {

$0.price >= min && $0.price <= max

}

}

}

ProductFilterForm can now be unit tested in isolation. The unit test is shown below:

func test_user_can_filter_products_by_price() throws {

self.continueAfterFailure = false

let products = [

Product(id: 1, title: "Product 1", price: 10),

Product(id: 2, title: "Product 2", price: 100),

Product(id: 3, title: "Product 3", price: 200),

Product(id: 4, title: "Product 4", price: 500)

]

let expectedFilteredProducts = [

Product(id: 2, title: "Product 2", price: 100),

Product(id: 3, title: "Product 3", price: 200),

Product(id: 4, title: "Product 4", price: 500)

]

let productFilterForm = ProductFilterForm(min: 100, max: 500)

let filteredProducts = productFilterForm.filterProducts(products)

for expectedProduct in expectedFilteredProducts {

let product = filteredProducts.first { $0.id == expectedProduct.id }

XCTAssertNotNil(product)

XCTAssertEqual(product!.title, expectedProduct.title)

XCTAssertEqual(product!.price, expectedProduct.price)

}

}

Unit testing view’s logic in isolation as shown above can be beneficial for complicated user interfaces. Keep in mind that just because your unit test passes, does not mean that your user interface is working as expected.

And the final kind of test you can write is an end-to-end test. E2E tests are great because they test the app from user’s point of view and they are best against regression. The downside is that E2E tests are slower then running unit tests. The main reason they are slower is because they are testing the complete application instead of small units. Most of the issues in software exists because the application was tested at unit level and not at system level. I encourage you to spend some time writing meaningful E2E tests.

Here is an implementation of an E2E test for the above scenario.

func test_user_can_filter_products_based_on_price() {

let app = XCUIApplication()

app.launchEnvironment = ["ENV": "TEST"]

app.launch()

app.textFields["minTextField"].tap()

app.textFields["minTextField"].typeText("100")

app.textFields["maxTextField"].tap()

app.textFields["maxTextField"].typeText("500")

app.buttons["applyButton"].tap()

// assert that the count is correct

XCTAssertEqual(3, app.collectionViews["productList"].cells.count)

// assert that the items are correct

XCTAssertEqual("Product 2", app.collectionViews["productList"].staticTexts["Product 2"].label)

XCTAssertEqual("Product 3", app.collectionViews["productList"].staticTexts["Product 3"].label)

XCTAssertEqual("Product 4", app.collectionViews["productList"].staticTexts["Product 4"].label)

}

In the end you will have to decide where in testing pyramid you want to invest your time to get the best return on your investment.

If you want to learn more about testing then you can check out my course Test Driven Development in iOS Using Swift.

Screens vs Views

When I was working with Flutter, I observed a common pattern for organizing the widgets. Flutter developers were separating the widgets based on whether the widgets represents an entire screen of just a reusable control. Since React, Flutter and SwiftUI are extremely similar in nature we can apply the same principles when building SwiftUI applications.

For example when displaying details of a movie, instead of calling that view MovieDetailView, you can call it MovieDetailScreen. This will make it clear that the detail view is an actual screen and not some reusable child view. Here are few more examples.

Screens

- MovieDetailScreen

- HomeScreen

- LoginScreen

- RegisterScreen

- SettingsScreen

Views

- RatingsView

- MessageView

- ReminderListView

- ReminderCellView

I find that it is always a good idea to keep a close eye on our friendly neighbors React and Flutter. You never know what ideas you will bring from other declarative frameworks into SwiftUI.

Validation

There is a famous saying in software development, garbage in, garbage out. This means if you allow users to enter incorrect information (garbage) through the user interface then that garbage will eventually end up in your database. And usually when this happens, it becomes extremely difficult and time consuming to clean the database.

You must take necessary steps to prevent users from submitting incorrect information in the first place.

Consider a simple LoginScreen view with username and password TextFields. If we want to enable the login Button only when the view is validated correctly, we can use the implementation below:

struct LoginScreen: View {

@State private var username: String = ""

@State private var password: String = ""

private var isFormValid: Bool {

!username.isEmptyOrWhiteSpace && !password.isEmptyOrWhiteSpace

}

var body: some View {

Form {

TextField("Username", text: $username)

TextField("Password", text: $password)

Button("Login") {

}.disabled(!isFormValid)

}

}

}

For such trivial logic, you can use Xcode Previews to quickly perform manual testing and validate the outcome.

If you are working on a more complicated form, then it is advised to extract it into its own struct. This concept is shown in the implementation below.

struct LoginFormConfig {

var username: String = ""

var password: String = ""

var isFormValid: Bool {

!username.isEmptyOrWhiteSpace && !password.isEmptyOrWhiteSpace

}

}

struct LoginScreen: View {

@State private var loginFormConfig: LoginFormConfig = LoginFormConfig()

var body: some View {

Form {

TextField("Username", text: $loginFormConfig.username)

TextField("Password", text: $loginFormConfig.password)

Button("Login") {

}.disabled(!loginFormConfig.isFormValid)

}

}

}

LoginFormConfig encapsulates the form validation. This also allows us to write unit tests against the LoginFormConfig. Few unit tests are shown below:

final class LearnTests: XCTestCase {

func test_login_form_validates_successfully() {

let expectedOutputs: [[String: Any]] = [

["username": "johndoe", "password": "password", "isFormValid": true],

["username": "", "password": "password", "isFormValid": false],

["username": "johndoe", "password": " ", "isFormValid": false],

["username": "", "password": " ", "isFormValid": false],

["username": " ", "password": "password", "isFormValid": false],

["username": " johndoe", "password": " password", "isFormValid": true]

]

for expectedOutput in expectedOutputs {

let username = expectedOutput["username"] as! String

let password = expectedOutput["password"] as! String

let isFormValid = expectedOutput["isFormValid"] as! Bool

let loginFormConfig = LoginFormConfig(username: username, password: password)

XCTAssertEqual(loginFormConfig.isFormValid, isFormValid)

}

}

}

In the end extracting the form validation into a separate struct and writing unit tests for it depends on your level of confidence. Simple forms can be tested easily through Xcode Previews and do not require additional structure or even unit tests.

Validation helper functions like isEmptyOrWhiteSpace, isNumeric, isEmail, isLessThan can be moved into a separate Swift package. This will promote reusability and other projects can also benefit from using it.

I covered few different ways of handling and displaying validation errors in one of my previous articles that you can read here.

Grouping View Events

One way to create reusable views in SwiftUI is to delegate the events to the parent view. This allows views to be used in different scenarios and without tying them to a particular logic. One way to accomplish this is to use closures.

Consider a ReminderCellView, which allows the user to perform check/uncheck and delete operations. The implementation is shown below:

struct ReminderCellView: View {

let index: Int

let onChecked: (Int) -> Void

let onDelete: (Int) -> Void

var body: some View {

HStack {

Image(systemName: "square")

.onTapGesture {

onChecked(index)

}

Text("ReminderCellView \(index)")

Spacer()

Image(systemName: "trash")

.onTapGesture {

onDelete(index)

}

}

}

}

ReminderCellView exposes onChecked and onDelete closures. The caller can use these closures to perform a particular task. The calling side is shown below:

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

List(1...20, id: \.self) { index in

ReminderCellView(index: index, onChecked: { index in

// do something

}, onDelete: { index in

// do something

})

}

}

}

As the complexity of ReminderCellView increases and it exposes more events then the calling side will become more complicated.

We can fix this issue by grouping all the events into a simple enum. This is shown below:

enum ReminderCellEvents {

case onChecked(Int)

case onDelete(Int)

}

The ReminderCellView can be updated to use ReminderCellEvents. This is shown below:

struct ReminderCellView: View {

let index: Int

let onEvent: (ReminderCellEvents) -> Void

var body: some View {

HStack {

Image(systemName: "square")

.onTapGesture {

onEvent(.onChecked(index))

}

Text("ReminderCellView \(index)")

Spacer()

Image(systemName: "trash")

.onTapGesture {

onEvent(.onDelete(index))

}

}

}

}

Now, instead of dealing with multiple closures we are only handling a single enum based event structure. The calling site also looks much cleaner.

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

List(1...20, id: \.self) { index in

ReminderCellView(index: index) { event in

switch event {

case .onChecked(let index):

print(index)

case .onDelete(let index):

print(index)

}

}

}

}

}

In the end you will have to decide when you want to group events into an enum and when you want to use them individually (multiple closures). I tend to prefer using enum events if I have more than two closures exposed by the view.

Navigation

SwiftUI introduced NavigationStack in iOS 16, which allowed developers to configure global routes for their application. This is similar to React Router, where routes can be configured in a single place. When I originally wrote this section, I used @EnvironmentObject to store the routes. Even though it worked as expected but it did not felt natural. The main purpose of @EnvironmentObject is to store state that will be shared with different views in the application. @EnvironmentObject can be really beneficial when you have to access state in a deeply nested view, without having to pass through all the parent views.

In terms of navigation, we are not sharing state with other views that will be displayed on the screen, we are sharing app environment configurations. For this scenario @Environment is a much better choice. @Environment values can be used to store configuration settings, services, application routers and more. You have already seen @Environment in action earlier when we stored httpClient as a custom environment value.

We will start by creating an enum to represent routes for our application.

enum Route: Hashable {

case home

case login

case detail(Product)

}

For larger apps you can create nested enums to divide the routes based on different sections of the application.

In my previous implementation, I was storing the closure associated with navigation directly in the Environment values. Some users suggested that this is not a good practice and it will cause unnecessary rendering of the views. I have personally not experienced any issues with the implementation but decided to update it to support structs as Environment value instead of closure.

NavigationAction struct will be responsible for storing the action associated with navigation. We will also utilize the SwiftUI built-in callAsFunction, which is invoked automatically when you create an instance of NavigationAction. The primary purpose of NavigationAction is to wrap the closure into an action. This allows us to store a value type struct in the Environment value as oppose to a closure. The implementation of NavigationAction is shown below:

struct NavigateAction {

typealias Action = (NavigationType) -> ()

let action: Action

func callAsFunction(_ navigationType: NavigationType) {

action(navigationType)

}

}

Next, we will implement custom Environment key and Environment values.

enum NavigationType: Hashable {

case push(Route)

case unwind(Route)

}

struct NavigateEnvironmentKey: EnvironmentKey {

static var defaultValue: NavigateAction = NavigateAction(action: { _ in })

}

extension EnvironmentValues {

var navigate: (NavigateAction) {

get { self[NavigateEnvironmentKey.self] }

set { self[NavigateEnvironmentKey.self] = newValue }

}

}

The important thing to notice here is the declaration and usage of NavigationType. The NavigationType enum represents the two types of navigation that can be performed. This includes the default push navigation and also unwind navigation. Unwind navigation will allow users to go from View G to View C or root.

If your application does not support unwind navigation then you can exclude

NavigationTypecompletely and directly useRouteinstead.

We will also implement a onNavigate function on the view. This will allow us to easily inject the required environment values.

extension View {

func onNavigate(_ action: @escaping NavigateAction.Action) -> some View {

self.environment(\.navigate, NavigateAction(action: action))

}

}

Next, we need to setup the routes and inject Environment values at the root of our application. Usually this is performed in the App file of your application. The implementation is shown below:

@main

struct LearnApp: App {

@State private var routes: [Route] = []

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

NavigationStack(path: $routes) {

ContentView()

.navigationDestination(for: Route.self) { route in

switch route {

case .home:

Text("HomeView")

case .login:

Text("LoginView")

case .detail(let product):

Text("ProductView \(product.name)")

}

}

}.onNavigate { navType in

switch navType {

case .push(let route):

routes.append(route)

case .unwind(let route):

if route == .home {

routes = []

} else {

guard let index = routes.firstIndex(where: { $0 == route }) else { return }

routes = Array(routes.prefix(upTo: index + 1))

}

}

}

}

}

}

The NavigationStack tracks the routes using the $routes binding. Whenever a new route is added or removed, .navigationDestination is validated. The .navigationDestination modifier is responsible for returning the destination view based on the type of the route. In a similar fashion, environment values are injected to the NavigationStack using the onNavigate function.

Finally, views can perform programmatic navigation using the new @Environment key called navigate. This is shown in the following implementation:

struct ReviewList: View {

@Environment(\.navigate) private var navigate

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Reviews")

Button("Go to Product") {

navigate(.push(.detail(Product(name: "Chair"))))

}

Button("Go back to Home View") {

navigate(.unwind(.home))

}

}

}

}

While researching for this section, I tried out various ways to perform routing. One of the solutions included the following easy to use syntax:

navigate(.detail(Product(name: "Chair")))

The problem I ran into was the above implementation did not supported unwinding routes. One way to handle unwinding would be to simply check the routes array and then if the route already exists then drop all the indexes after that route. Although this can be implemented but it makes code unclear to the developer. Take a look at the following example:

navigate(.reviews)

When the developer composes this code, the assumption is that it facilitates push navigation rather than unwinding. However, if the same function call is employed to execute an unwind operation exclusively in cases where the route already exists, it imposes an additional cognitive burden on the developer. Consequently, the developer is compelled to possess a more comprehensive understanding of the inner workings of the function before initiating its invocation.

So, in the end it depends on your needs. If you have criteria to support unwinding routes then use the implementation above, on the other hand if you are just interested in normal push navigation then substitute NavigationType in navigate closure with Route.

Navigation with TabViews

The above technique will not work, when your app contain tab views and wants to perform programmatic navigation. The main reason is that each tab needs to hold a separate navigation stack so it can track navigation history independently.

Let’s first start by creating tabs for our application. Each tab can be represented by a case in an enum as shown below:

enum AppScreen: Hashable, Identifiable, CaseIterable {

case backyards

case birds

case plants

var id: AppScreen { self }

}

You can also extend AppScreen enum to add support for labels and destination. This is shown below:

extension AppScreen {

@ViewBuilder

var label: some View {

switch self {

case .backyards:

Label("Backyards", systemImage: "tree")

case .birds:

Label("Birds", systemImage: "bird")

case .plants:

Label("Plants", systemImage: "leaf")

}

}

@ViewBuilder

var destination: some View {

switch self {

case .backyards:

BackyardNavigationStack()

case .birds:

BirdsNavigationStack()

case .plants:

PlantsNavigationStack()

}

}

}

The important part to note is the destination property. This property is responsible for returning the navigation stack based on the tab selected by the user. Since each tab will have its own navigation stack, it will maintaining its own navigation history.

Once we are done with our AppScreen enum, we can display the tabs in our view.

struct AppTabView: View {

@Binding var selection: AppScreen?

var body: some View {

TabView(selection: $selection) {

ForEach(AppScreen.allCases) { screen in

screen.destination

.tag(screen as AppScreen?)

.tabItem { screen.label }

}

}

}

}

The history of each tab will be maintained by Router. Route is simply an Observable, which is injected as a global state. The implementation is shown below:

@Observable

class Router {

var birdRoutes: [BirdRoute] = []

var plantRoutes: [PlantRoute] = []

}

If you find a way to expose Router as an EnvironmentValue instead of EnvironmentObject then let me know. It will read and look much better as an EnvironmentValue rather than EnvironmentObject.

The routes for each navigation stack are implemented below:

enum PlantRoute {

case home

case detail

}

struct Bird: Hashable {

let name: String

}

enum BirdRoute: Hashable {

case home

case detail(Bird)

}

And finally, here is the implementation of PlantsNavigationStack which uses the router from the Environment.

struct PlantsNavigationStack: View {

@Environment(Router.self) private var router

var body: some View {

@Bindable var router = router

NavigationStack(path: $router.plantRoutes) {

Button("Plants Go to detail") {

router.plantRoutes.append(.detail)

}.navigationDestination(for: PlantRoute.self) { route in

switch route {

case .home:

Text("Home")

case .detail:

Text("Plant Detail")

}

}

}

}

}

Keep in mind that you only need router for dynamic routes. Normal routes utilize the

navigationDestinationview modifier.

That’s it!

If you are interested in watching a video on this then check out Programmatic Routing in SwiftUI for TabView Apps in SwiftUI.

I published a course on SwiftUI Navigation called SwiftUI Navigation Fundamentals - Beginner’s Guide, which covers different navigation scenarios.

Displaying Errors

Displaying errors is an integral part of any application. In SwiftUI we have many different ways of displaying errors. In this section, we will cover three different techniques that can be used to display errors.

Technique #1:

This technique was demonstrated in Apple’s Scrumdinger application. We will start by creating an ErrorWrapper, which will be responsible for wrapping the actual error and also providing guidance to the user on the next steps. The implementation is shown below:

struct ErrorWrapper: Identifiable {

let id = UUID()

let error: Error

let guidance: String

}

ErrorView is responsible for displaying the details of the error in a visual format. You can find basic implementation of an ErrorView below.

struct ErrorView: View {

let errorWrapper: ErrorWrapper

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Error has occured in the application.")

.font(.headline)

.padding([.bottom], 10)

Text(errorWrapper.error.localizedDescription)

Text(errorWrapper.guidance)

.font(.caption)

}.padding()

}

}

ErrorView is simply a view and you can customize it as much as you want.

The usage of ErrorWrapper and ErrorView is shown below:

struct HomeView: View {

@State private var errorWrapper: ErrorWrapper?

private enum SampleError: Error {

case operationFailed

}

var body: some View {

VStack {

Button("Throw Error") {

do {

throw SampleError.operationFailed

} catch {

errorWrapper = ErrorWrapper(error: error, guidance: "Operation failed. Please try again.")

}

}

}.sheet(item: $errorWrapper) { errorWrapper in

ErrorView(errorWrapper: errorWrapper)

}

}

}

Now, when an error is thrown a sheet is presented with the details about the error along with the guidance for next steps.

At present, when the intention is to present an error in a distinct view, the process necessitates the creation of an “errorWrapper” along with the attachment of a sheet to the corresponding view for the error’s visibility. But imagine a scenario where the display of errors could be consolidated into a centralized location.

Technique #2:

Instead of attaching the sheet/alert to each screen of the application, we can attach it to the root view. This way we have a single place to handle, displaying of the errors. For this to work, we need global access to the errorWrapper so it can be set by any view. We will use the same technique we used in the Navigation section and use a custom @Environment value to manage global access. The implementation for the custom key and the extension is shown below:

struct ShowErrorEnvironmentKey: EnvironmentKey {

static var defaultValue: (Error, String) -> Void = { _, _ in }

}

extension EnvironmentValues {

var showError: (Error, String) -> Void {

get { self[ShowErrorEnvironmentKey.self] }

set { self[ShowErrorEnvironmentKey.self] = newValue }

}

}

Now, we can use the showError Environment value in your view as implemented below:

struct HomeView: View {

@Environment(\.showError) private var showError

private enum SampleError: Error {

case operationFailed

}

var body: some View {

VStack {

Button("Throw Error") {

do {

throw SampleError.operationFailed

} catch {

showError(error, "Please try again later.")

}

}

}

}

}

Finally, will will attach the new Environment value to the root view of the application so it is easily accessible by all child views.

@main

struct LearnApp: App {

@State private var errorWrapper: ErrorWrapper?

var body: some Scene {

WindowGroup {

ContentView()

.environment(\.showError) { error, guidance in

errorWrapper = ErrorWrapper(error: error, guidance: guidance)

}

.sheet(item: $errorWrapper) { errorWrapper in

Text(errorWrapper.error.localizedDescription)

}

}

}

}

We have now centralized the displaying of errors for our application. In the future if you want to make any changes then there is a single place you can update.

New displays like .alert, .toast etc can be added by introducing an enum to the ErrorWrapper. You can check out the implementation here.

Technique #3:

I learned about this technique from my discussion with Hussein EIRyalat. He used custom view modifiers to display of errors. I have changed the implementation a little bit to support ErrorWrapper.

The first step is to implement the view modifiers and view extensions. The implementation is shown below:

struct ErrorViewModifier: ViewModifier {

@Binding var errorWrapper: ErrorWrapper?

init(errorWrapper: Binding<ErrorWrapper?>) {

self._errorWrapper = errorWrapper

}

func body(content: Content) -> some View {

content

.sheet(item: $errorWrapper) { errorWrapper in

Text(errorWrapper.error.localizedDescription)

}

}

}

extension View {

func onError(_ errorWrapper: Binding<ErrorWrapper?>) -> some View {

modifier(ErrorViewModifier(errorWrapper: errorWrapper))

}

}

Now, we can directly call onError as shown in the implementation below:

struct HomeView: View {

@State private var errorWrapper: ErrorWrapper?

private enum SampleError: Error {

case operationFailed

}

var body: some View {

VStack {

Button("Throw Error") {

do {

throw SampleError.operationFailed

} catch {

errorWrapper = ErrorWrapper(error: error, guidance: "Please try again.")

}

}

}.onError($errorWrapper)

}

}

In this section, we covered three different ways of displaying errors in our SwiftUI application. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. Try out different approaches and see which one fits your needs.

Formatting

It is common practice to format the data before presenting it to the user.

When formatting data, it’s crucial to exercise caution with regard to the user’s present locale. Take a look at the following example.

struct HomeView: View {

let amount: Double = 25.75

var body: some View {

// displays $25.750000

Text("$\(amount)")

}

}

There are few problems with the above implementation. The first one is pretty basic. Users don’t want to see $25.750000 they want to see $25.75. But the much bigger issue is the hard-coded $ sign. This means that the amount will only be displayed in US dollar currency. It would be a much better idea to set the currency based on user’s locale.

The following implementation shows how to display currency correctly based on user’s locale.

extension Locale {

static var currencyCode: String {

Locale.current.currency?.identifier ?? "USD"

}

}

struct HomeView: View {

let amount: Double = 25.75

var body: some View {

// displays $25.75

Text(amount, format: .currency(code: Locale.currencyCode))

}

}

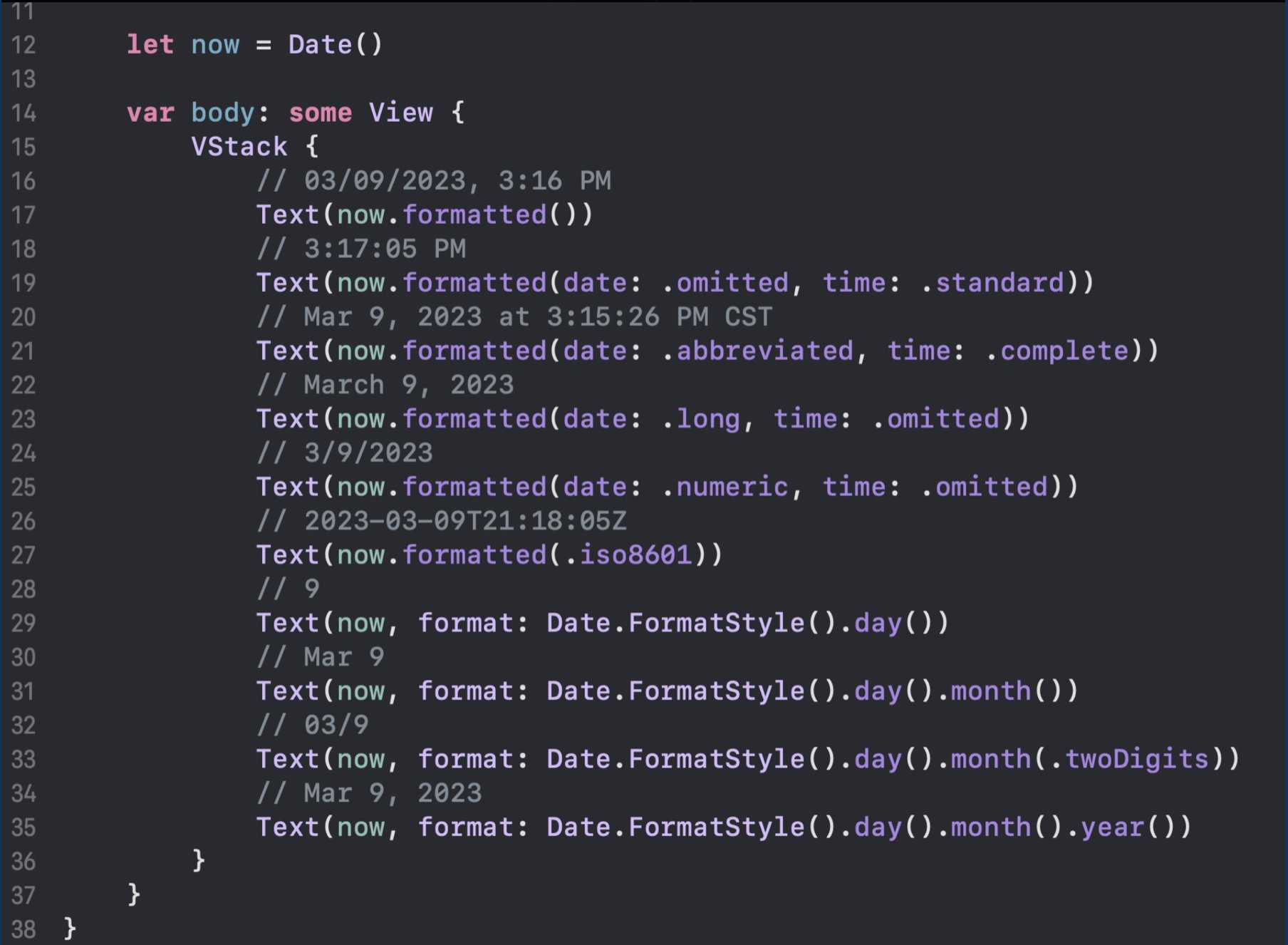

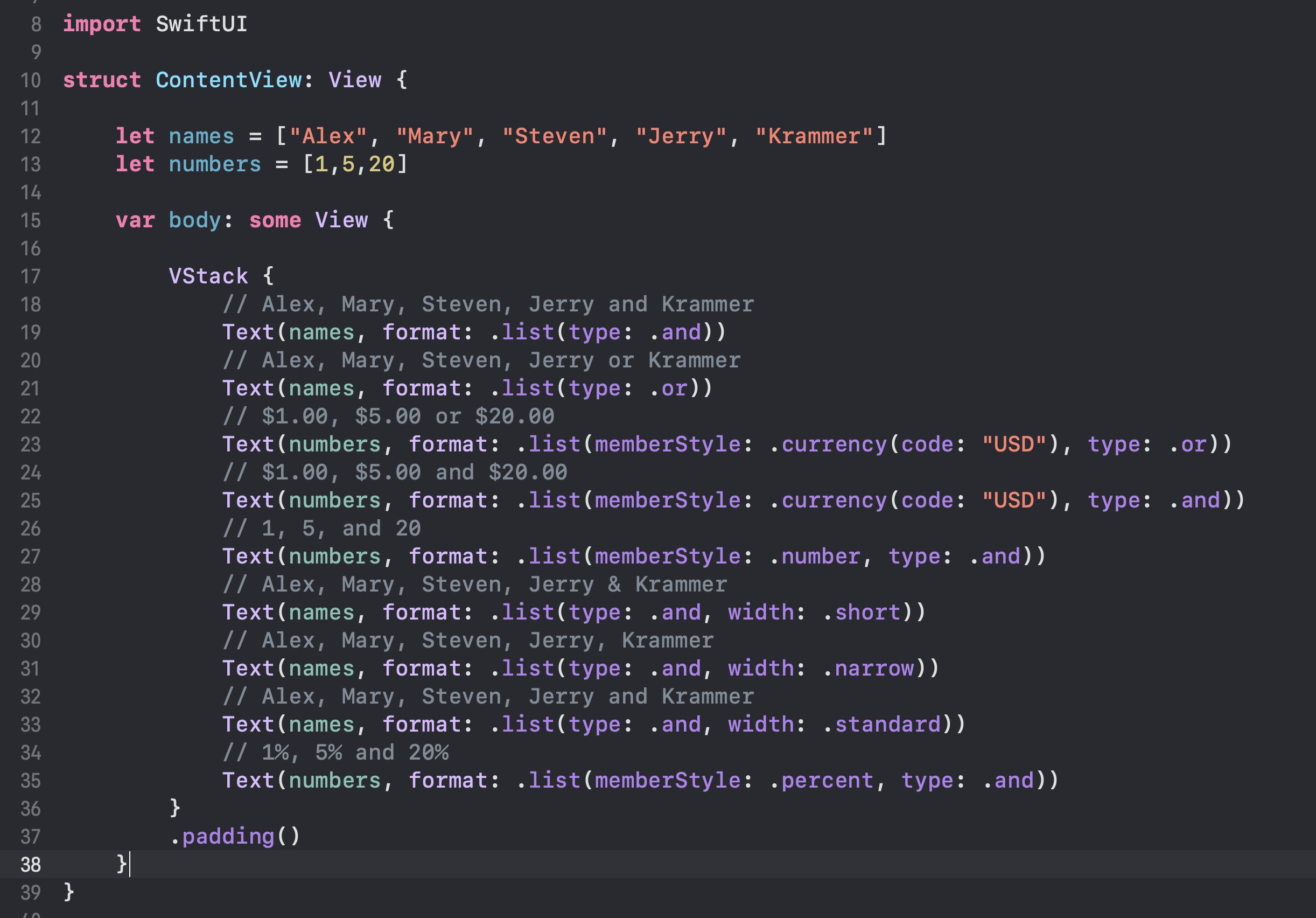

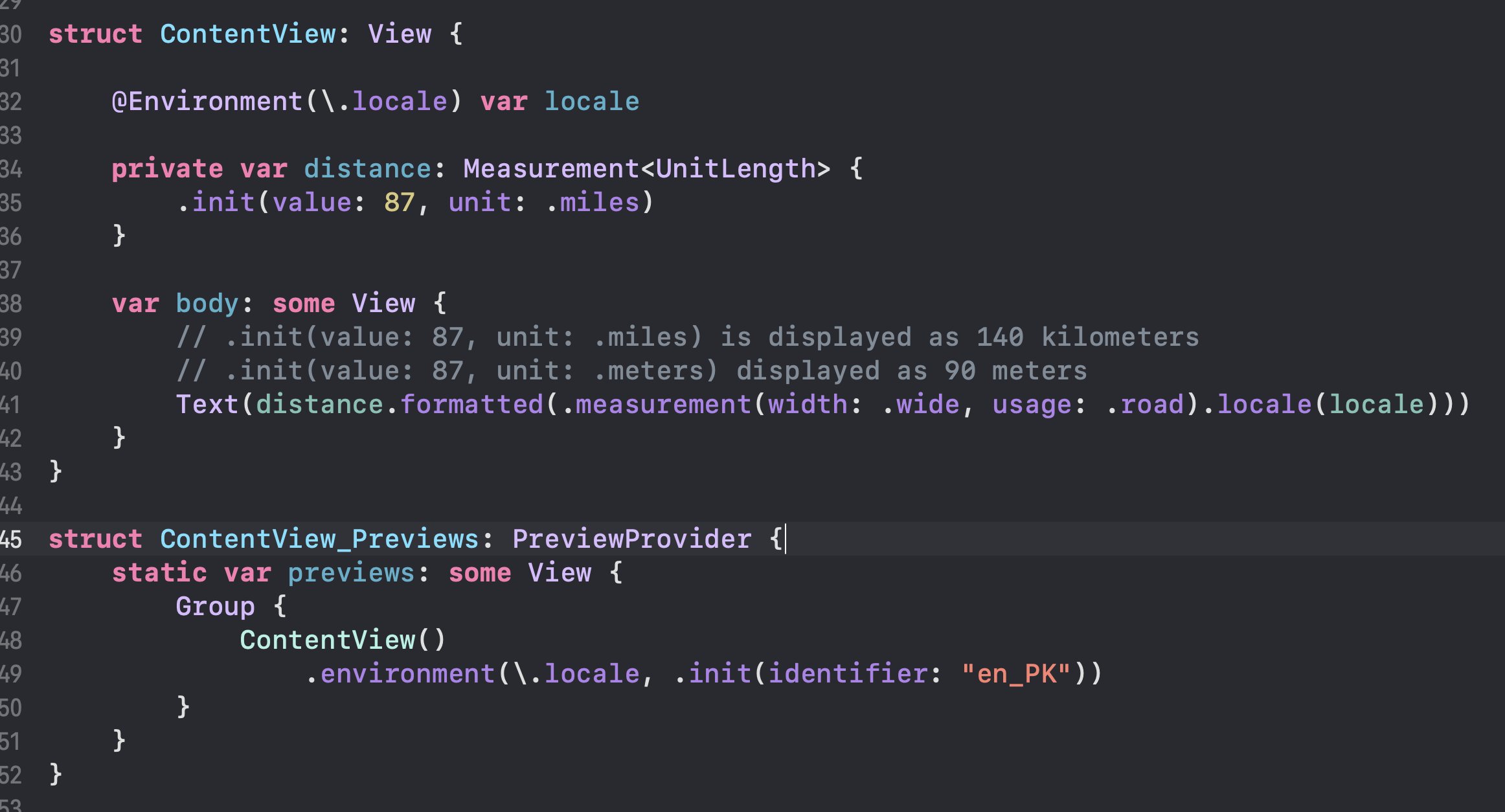

Formatting in SwiftUI is not just limited to currency but you can format dates, measurements and even lists. This is shown below:

Formatting Dates:

Formatting Lists:

Formatting Distances:

You don’t need to access locale from @Environment. This was just used to demonstrate that it converts distances automatically based on the locale.

So, the next you are trying to format your data to be displayed in a SwiftUI view make sure to check out the built-in formatters. There is a very good chance that SwiftUI already provides utility functions for your needs.

Testing

This section of the article is taken from my post Pragmatic Testing and Avoiding Common Pitfalls

The main purpose of writing tests is to make sure that the software works as expected. Tests also gives you confidence that a change you make in one module is not going to break stuff in the same or other modules.

Not all applications requires writing tests. If you are building a basic application with a straight forward domain then you can test the complete app using manual testing. Having said that in most professional environments, you are working with a complicated domain with business rules. These business rules form the basis on which company operates and generates revenue.

In this article, I will discuss different techniques of writing tests and how a developer can write good tests to get the most return on their investment.

Not all tests are created equal

Consider a scenario that you are writing an application for a bank. One of the business rules is to charge overdraft fees in case of insufficient funds. Banks generate billions of dollars income by just fees alone. As a developer, you must write good quality tests to make sure that overdraft fee calculation works as expected.

In the same bank app, you may have features like rendering templates for emails or logging certain interactions. These features are important but may not produce the same return on investment as compared to charging overdraft fees. This means if the email template is not in the correct format then the banks are not going to loose millions of dollars and you will not receive a call in the middle of the night. If the logging is meant for developers then in most cases you don’t even need to write tests for it. It is just an implementation detail.

If you are building a logging framework then it is essential that you thoroughly test the public API exposed by your framework.

Next time you are writing a test, ask yourself how important this feature is for the business. If it is an integral part of the business then make sure to test it thoroughly and go for high code coverage.

Test behavior not implementation

One of the biggest mistakes developers make is to focus on writing tests against the implementation details instead of the behavior of the application.

A trigger to add a new test is the requirement, not a class or a function.

Just because you added a new class or a function does not mean that you will start writing tests. That is just an implementation detail which can change overtime. Your tests should target the business requirements and not the implementation details.

Here are few examples of behaviors, derived from business requirements:

- When a customer withdraw amount and has insufficient funds then charge an overdraft fee.

- The number of stocks specified by customer are submitted for trade at a specified price, once the limit has reached.

The behavior stems from the requirement of the project. Tests that checks the implementation details instead of the behavior tends to be very brittle and can easily break when the implementation changes even though the behavior remains the same.

Let’s consider a scenario, where you are building an application to display a list of products on the screen. The products are fetched from a JSON API and rendered using SwiftUI framework, following the principles of MVVM design pattern.

First we will look at a common way of testing the above scenario that is adopted by most developers and then later we will implement tests in a more pragmatic way.

The complete app might look like the implementation below:

class Webservice {

func fetchProducts() async throws -> [Product] {

// ignore the hard-coded URL. We can inject the URL from using test configuration.

let url = URL(string: "https://test.store.com/api/v1/products")!

let (data, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(from: url)

return try JSONDecoder().decode([Product].self, from: data)

}

}

class ProductListViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var products: [ProductViewModel] = []

func populateProducts() async {

do {

let products = try await Webservice().fetchProducts()

self.products = products.map(ProductViewModel.init)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

struct ProductViewModel: Identifiable {

private let product: Product

init(product: Product) {

self.product = product

}

var id: Int {

product.id

}

var title: String {

product.title

}

}

struct ProductListScreen: View {

@StateObject private var vm = ProductListViewModel()

var body: some View {

List(vm.products) { product in

Text(product.title)

}.task {

await vm.populateProducts()

}

}

}

The above application works as expected and produces the expected result. Instead of testing the concrete implementation of the Webservice, we will introduce an interface/contract/protocol just so that we can inject a mock. The sole purpose of creating the protocol is to satisfy the tests, even though there is only one concrete implementation that conforms to that protocol/interface.

This is called Test Induced Damage. The tests are dictating that we should add dependencies so you can mock out the service. The only purpose of introducing a protocol/contract/interface is so you can eventually mock it. Keep in mind there is nothing wrong with using protocols/contracts in your application. They do serve a very important purpose to hide the implementation details from the user and providing abstraction, but just to add contracts to satisfy testing goals in not a good practice as it complicates the implementation and your tests are directed away from testing the actual behavior of the app.

In the code below we have introduced a WebserviceProtocol. Both Webservice and the newly created MockedWebservice conforms to the WebserviceProtocol as shown below:

protocol WebserviceProtocol {

func fetchProducts() async throws -> [Product]

}

class Webservice: WebserviceProtocol {

func fetchProducts() async throws -> [Product] {

let url = URL(string: "https://test.store.com/api/v1/products")!

let (data, _) = try await URLSession.shared.data(from: url)

return try JSONDecoder().decode([Product].self, from: data)

}

}

class MockedWebService: WebserviceProtocol {

func fetchProducts() async throws -> [Product] {

return [Product(id: 1, title: "Product 1"), Product(id: 2, title: "Product 2")]

}

}

You should probably use a better name, instead of calling it WebserviceProtocol. The main reason, I am calling it WebserviceProtocol is just for the sake of simplicity and convenience.

The webservice is now injected as a dependency to our ProductListViewModel. This is shown below:

class ProductListViewModel: ObservableObject {

private let webservice: WebserviceProtocol

@Published var products: [ProductViewModel] = []

init(webservice: WebserviceProtocol) {

self.webservice = webservice

}

func populateProducts() async {

do {

let products = try await Webservice().fetchProducts()

self.products = products.map(ProductViewModel.init)

} catch {

print(error)

}

}

}

The view, ProductListScreen is also updated to reflect the change.

struct ProductListScreen: View {

@StateObject private var vm = ProductListViewModel(webservice: WebserviceFactory.create())

var body: some View {

List(vm.products) { product in

Text(product.title)

}.task {

await vm.populateProducts()

}

}

}

WebserviceFactory is responsible for either returning the Webservice or MockedWebservice, depending on the application environment.

Now, let’s go ahead and check out the test.

final class ProductsTests: XCTestCase {

func test_populate_products() async throws {

let mockedWebService = MockedWebService()

let productListVM = ProductListViewModel(webservice: mockedWebService)

await productListVM.populateProducts()

// This line is verifying the implementation detail.

// Implementation details can change

// fetchProducts can change to getProducts and the test will fail.

verify(mockedWebService.fetchProducts()).wasCalled()

XCTAssertEqual(2, productListVM.products.count)

}

}

We created an instance of MockedWebservice inside our test and pass it to the ProductListViewModel. Next, we invoke the populateProducts function on the view model and then check to make sure that the fetchProducts on the mockedWebservice instance was called. Finally, the test checks the products property of the ````ProductListViewModel``` instance to make sure that is is populated correctly.

The problem with the above test is that it is not testing the behavior but the implementation. The following line of code is an implementation detail.

verify(mockedWebService.fetchProducts()).wasCalled()

This means if you decide to refactor your code and rename the function fetchProducts to getProducts then your test will fail. These kind of tests are often known as brittle tests as they break when the internal implementation changes even though the functionality/behavior provided by the API remains the same. This is also the main reason that your test should validate the behavior instead of the implementation.

The code that you write is a liability, including tests. When writing tests, focus on the quality of the tests instead of the quantity. Remember, you are not only responsible for writing tests but also maintaining them.

If you are using MVVM pattern then your VM may have logic. It is perfectly fine to write unit tests against the logic contained in the view model.

End to End Testing

In the previous section, you learned that and mocking in most scenarios does not provide the return on your investment. Tests written that use mocking usually end up being too brittle and can fail because of refactoring, breaking all the dependent tests even though the behavior remained the same.

Human psychology also plays an important role when writing tests. As software developers we want fast feedback with small amounts of dopamine hit along the way. There is nothing wrong with receiving fast feedback. Fast feedback is one of the important characteristics of a unit test. Unfortunately, sometimes we are going too fast to realize that we were on the wrong path. We start behaving like a test addict, who wants to see green checkmarks alongside the tests instantly.

As explained earlier adding tests that test the implementation details instead of behavior does not provide any benefit to your project. It may even work against you in the long run since now you will be responsible for maintaining those test cases and anytime the implementation detail changes, all your test will break even though the functionality remained the same.

I am not proposing that you should not write unit tests. Unit tests are great when you are testing small units of code. I am proposing that you must make sure that you are testing the behavior of the code and not implementation details. This means if you want to write unit tests for your view models, you can.

Apart from unit tests and integration tests, end to end tests are best against regression. A good end to end will test one complete story/behavior. Below you can find the implementation of an end to end test.

final class ProductTests: XCTestCase {

private var webservice: Webservice!

// products

let products = [Product(id: 1, title: "Handmade Fresh Table"),Product(id: 2, title: "Durable Water Bottle")]

override func setUp() {

// make sure the Webservice is using the TEST server endpoints and not PRODUCTION

webservice = Webservice()

// add few products // seeding the database

for product in products {

await webservice.addProduct(product: product)

}

}

func test_display_list_of_all_products() async {

let app = XCUIApplication()

app.launch()

let productList = app.tables["productList"]

// check if the item numbers is correct

XCTAssertEqual(productList.tables.cells.count, 2)

// check if the correct items are displayed

for(index, product) in products.enumerated() {

let cell = productList.cells.element(boundBy: index)

XCTAssertEqual(cell.staticTexts["productTitle"].label, product.title)

}

}

override func tearDown() async throws {

// make sure to delete ALL records from the database so future test results are not influenced

await webservice.deleteProductById(productId: 1)

await webservice.deleteProductById(productId: 2)

}

}